5-minute read

Say fossils and what comes to mind are the big, the bad, and the sexy: dinosaurs, pterosaurs, marine reptiles—in short, macrofossils. But perhaps more important and certainly more numerous are the microfossils. Fossils so small that you need a microscope to see them. In this richly illustrated book, French geologist and micropalaeontologist Patrick De Wever offers bite-sized insights into a discipline that rarely gets mainstream attention but undergirds many human endeavours.

Marvelous Microfossils: Creators, Timekeepers, Architects, written by Patrick De Wever, published by Johns Hopkins University Press in April 2020 (hardback, 256 pages)

Marvelous Microfossils immediately reminded me of Christian Sardet’s Plankton published by the University of Chicago Press in 2015. Both are large-format illustrated books on a mostly invisible world, originally published in French, that were picked up by American university presses. De Wever’s book was first published in 2016 by Biotope Éditions as Merveilleux Microfossiles and has now been published in English by Johns Hopkins University Press.

The book follows a straightforward structure. Four thematic sections each consist of short, one-page vignettes on a certain topic with illustrations and photos on the facing page. A first section introduces the various microscopic techniques used to study microfossils, as well as their living counterpart, plankton. One vignette covers the birth of oceanography, notably the 1872–1876 H.M.S. Challenger Expedition, another later deep-sea drilling projects such as Glomar Challenger and JOIDES Resolution.

The book follows a straightforward structure. Four thematic sections each consist of short, one-page vignettes on a certain topic with illustrations and photos on the facing page. A first section introduces the various microscopic techniques used to study microfossils, as well as their living counterpart, plankton. One vignette covers the birth of oceanography, notably the 1872–1876 H.M.S. Challenger Expedition, another later deep-sea drilling projects such as Glomar Challenger and JOIDES Resolution.

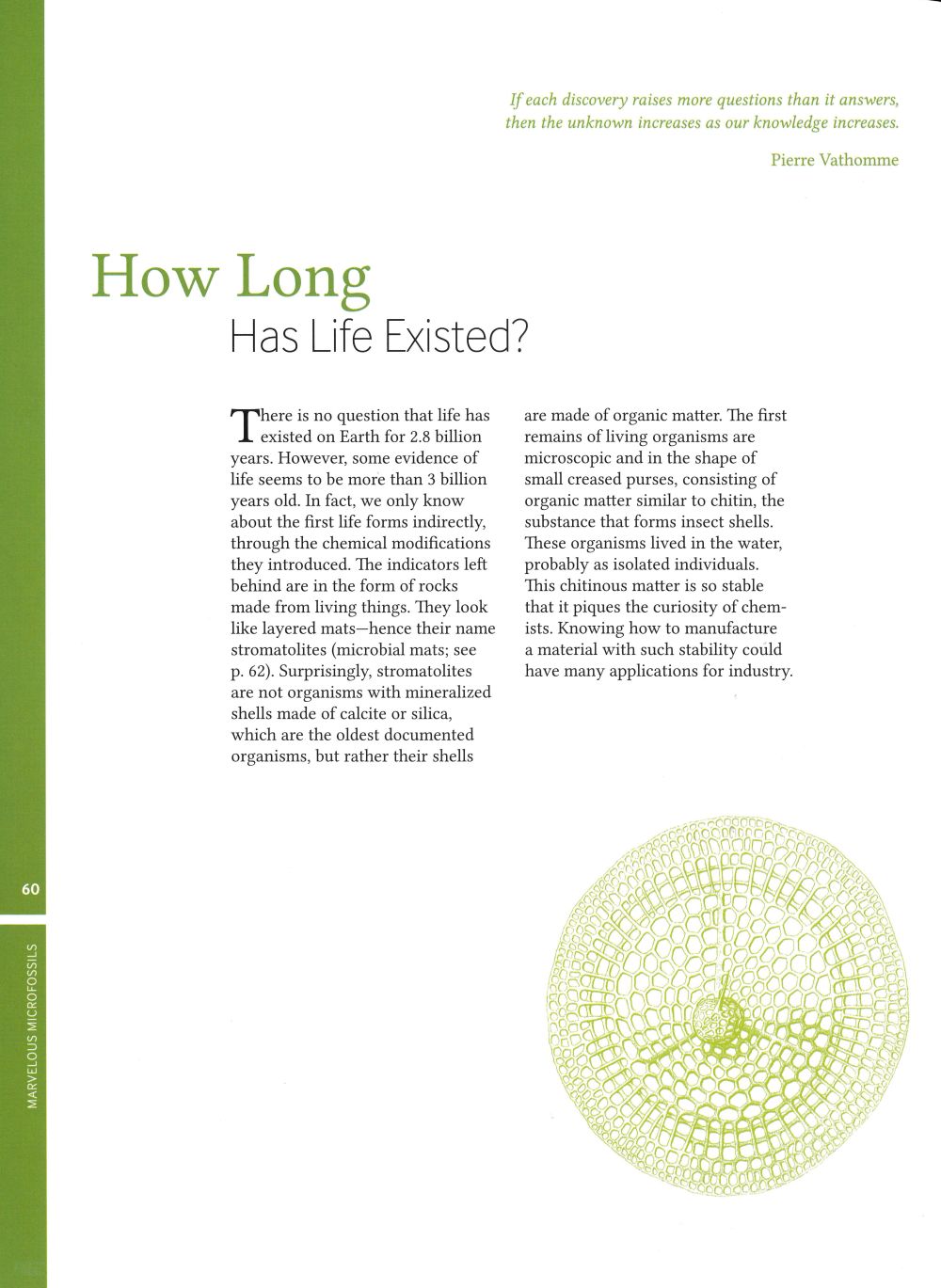

A second section touches on the deep history of life and our planet as told through microfossils. Some of the oldest fossils, at 3.5 billion years old, were formed by thin films of photosynthetic cyanobacteria that trapped sediment and, layer by layer, slowly formed rocky accretions known as stromatolites. Other important chapters are the Great Oxygenation Event some 2.3 billion years ago when atmospheric oxygen levels rose dramatically, in the process rusting the planet’s iron reserves and forming the banded iron formations that we mine to this day. Another side-effect was the Huronian glaciation which turned our planet into a “Snowball Earth”. There was the formation of the ozone layer which allowed life to flourish closer to and ultimately on the surface, the contribution of plankton to fossil fuel reserves, and so forth.

“Who [are] these microfossils [?] […] Mostly, they are members of the plankton community; the often translucent, near-invisible microorganisms that drift on ocean […] currents”

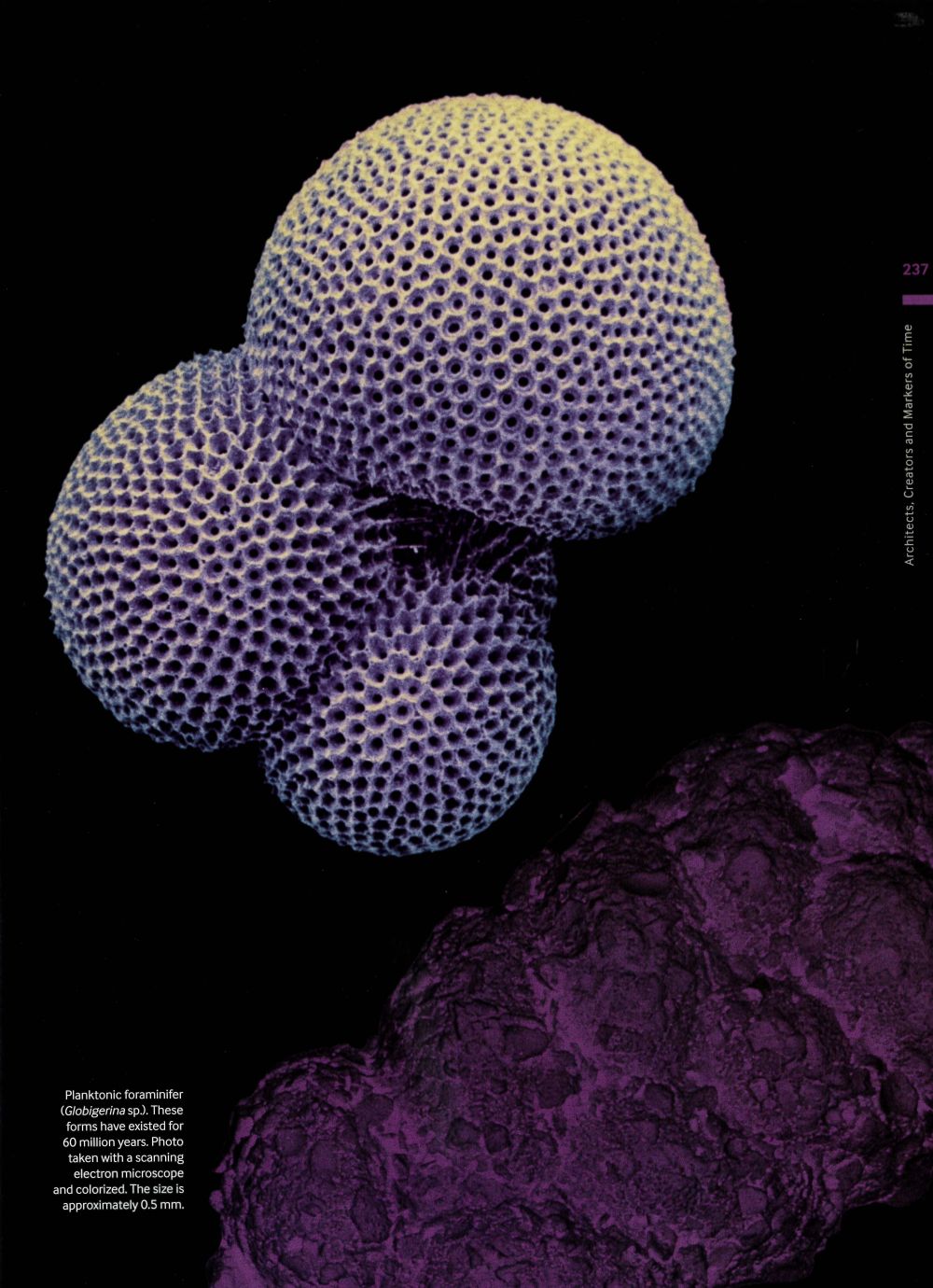

All of these subjects are deeply fascinating, and some have been the subject of excellent popular academic books. I cannot help but feel that De Wever’s vignettes are so brief as to barely scratch the surface. That said, where this approach comes into its own is the third part of the book where he surveys the diversity of microfossils. By now you may well be wondering who these microfossils are, what organisms they consist of. I would have started the book with this section. Mostly, they are members of the plankton community; the often translucent, near-invisible microorganisms that drift on ocean and freshwater currents. This encompasses phytoplankton capable of photosynthesis such as cyanobacteria, diatoms, dinoflagellates, and coccolithophores. But also numerous small animals: copepods and ostracods (tiny crustaceans), pteropods (tiny molluscs), sponges, foraminifera (amoeboid protists dressed in filigree skeletons known as tests), the very spiny radiolarians, more mysterious groups such as acritarchs and conodonts, and many others. Their dead bodies continuously rain down in the water column, with time forming sediments and rocks all of their own.

All of these subjects are deeply fascinating, and some have been the subject of excellent popular academic books. I cannot help but feel that De Wever’s vignettes are so brief as to barely scratch the surface. That said, where this approach comes into its own is the third part of the book where he surveys the diversity of microfossils. By now you may well be wondering who these microfossils are, what organisms they consist of. I would have started the book with this section. Mostly, they are members of the plankton community; the often translucent, near-invisible microorganisms that drift on ocean and freshwater currents. This encompasses phytoplankton capable of photosynthesis such as cyanobacteria, diatoms, dinoflagellates, and coccolithophores. But also numerous small animals: copepods and ostracods (tiny crustaceans), pteropods (tiny molluscs), sponges, foraminifera (amoeboid protists dressed in filigree skeletons known as tests), the very spiny radiolarians, more mysterious groups such as acritarchs and conodonts, and many others. Their dead bodies continuously rain down in the water column, with time forming sediments and rocks all of their own.

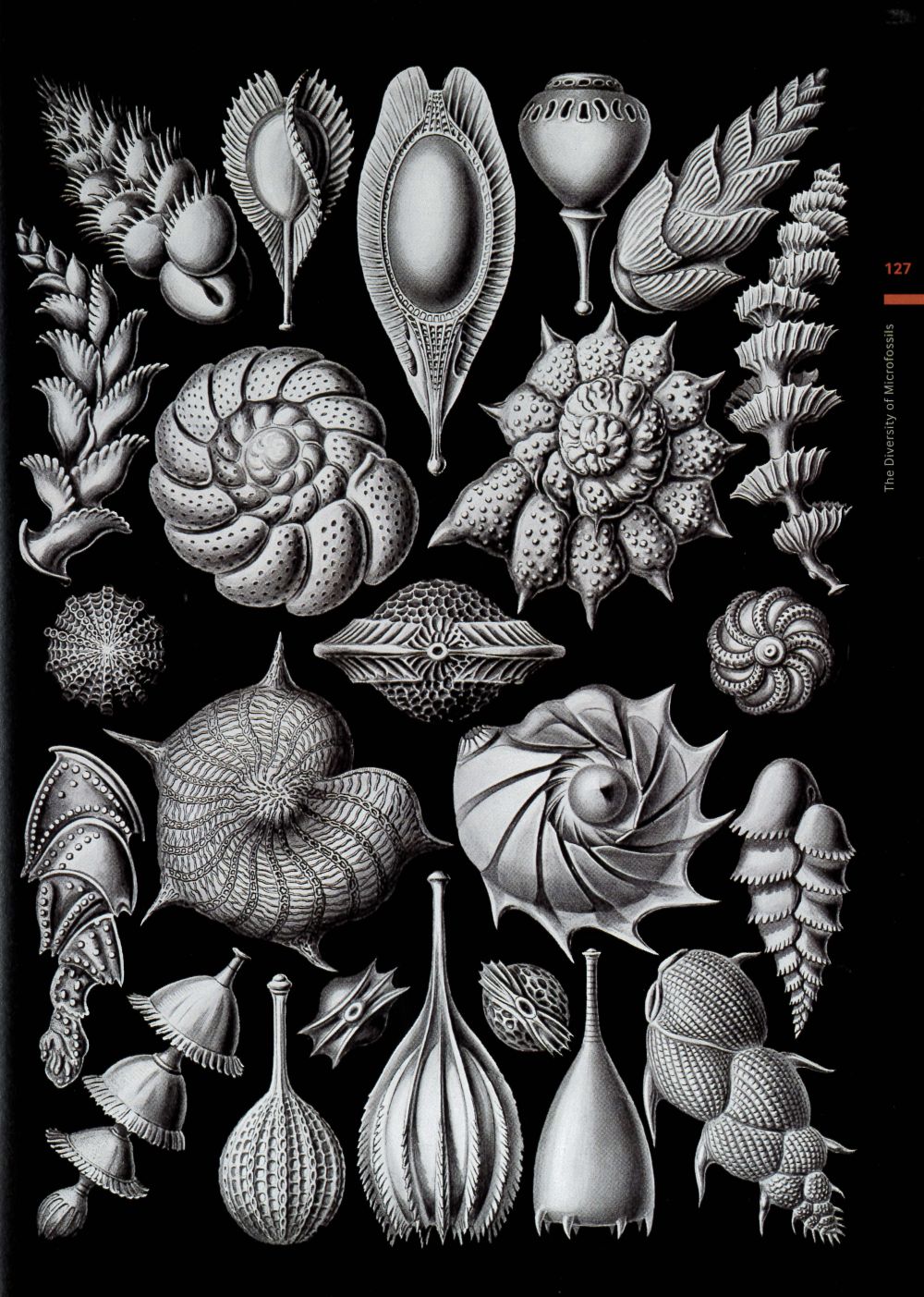

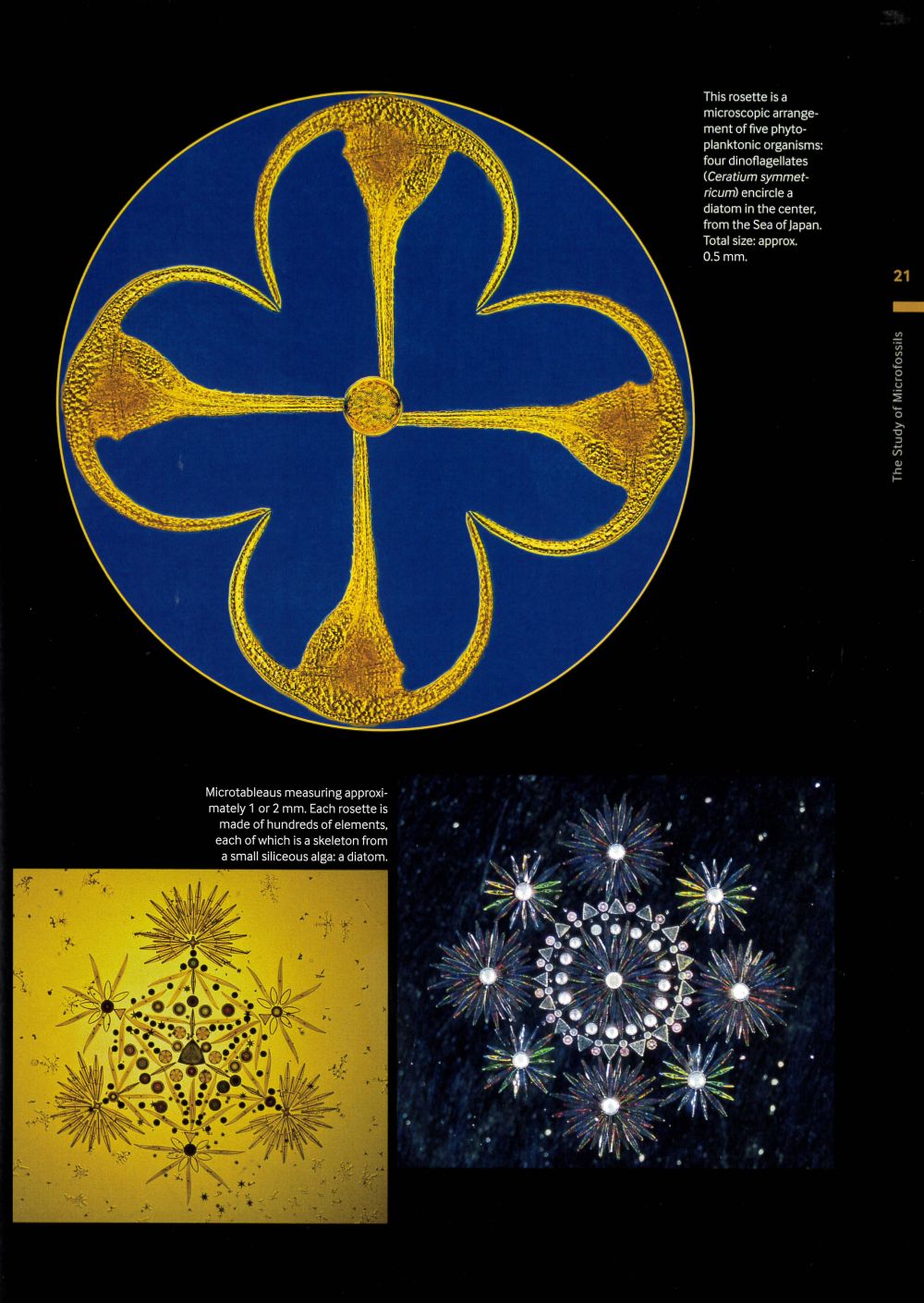

The diversity of these groups is wild and the variation in shape and morphology defies the imagination. Seeing is believing, however, and the book includes a large number of photos and illustrations to help with that. Next to numerous (electron) microscope photos, De Wever draws heavily on the many drawings of the famed 19th-century German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, with over a third of the illustrations here from his oeuvre.  Next to an influential biologist, he was also a skilled artist. Books such as Kunstformen der Natur and his illustrations for the reports of the Challenger expedition marry art and science.

Next to an influential biologist, he was also a skilled artist. Books such as Kunstformen der Natur and his illustrations for the reports of the Challenger expedition marry art and science.

Haeckel makes a return in the book’s last part, which looks at how microfossils, buoyed by Haeckel’s fame, influenced 19th century (French) art and architecture, notably Art Nouveau. There are also glimpses, all too brief, of other fascinating artists who painstakingly arrange microfossils under the microscope into geometrically mesmerising microtableaux (seen on the cover) or carve delicate scaled-up wooden versions of marine plankton.

“Patrick De Wever offers bite-sized insights into a discipline that rarely gets mainstream attention but undergirds many human endeavours.”

Last but not least, microfossils are economically incredibly important. As they are so numerous and their morphology evolves quickly, they make good markers for biostratigraphy, i.e. for determining the age of rock layers based on their fossil contents. The latter is vital when searching for petroleum and minerals, or for large engineering projects where you need to know on what rock layers you are constructing heavy infrastructure and buildings. Due to their ubiquity, foraminifera and diatoms are particularly useful groups.

There are very few popular books on micropalaeontology. Beyond the rare introductory textbook or welcome introductory guide to, say, diatoms, you will quickly find yourself confronted with journal articles and technical monographs, e.g. the long-running monograph series Bibliotheca Diatomologica from the German publisher Schweizerbart, and the Iconographia Diatomologica and Diatom Monograph series from Koeltz Scientific Books.

There are very few popular books on micropalaeontology. Beyond the rare introductory textbook or welcome introductory guide to, say, diatoms, you will quickly find yourself confronted with journal articles and technical monographs, e.g. the long-running monograph series Bibliotheca Diatomologica from the German publisher Schweizerbart, and the Iconographia Diatomologica and Diatom Monograph series from Koeltz Scientific Books.

In conclusion, Marvelous Microfossils is worth it for the illustrations alone and is readily accessible to readers with little to no background in geology, palaeontology, or marine biology. Although I would have liked more substance than the short vignettes De Wever provides, I cannot deny that he here unlocks for a general audience an academic discipline that is normally largely ignored outside of the professional community.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Thank you for this review! I have been studying microfossils and this book will be perfect for me. I upload my microfossil finds via 2×109.org and am amazed at the variety of life so long ago.

Thank you for spreading this awesome knowledge! Keep it up.

LikeLike