Underground spaces exert a strong pull on the imagination of most people, although for some this morphs into a fascination bordering on the obsessive. American author Will Hunt is one such person, part of a worldwide community of urban explorers who infiltrate into “the city’s obscure layers”. Though this encompasses more than underground spaces, they are a big part of it, and this book is Hunt’s story of how he fell in love with them. It is one of two big books published only five months apart on the subterranean realm, and I previously reviewed Robert Macfarlane’s Underland: A Deep Time Journey. Here I will turn my attention to Underground.

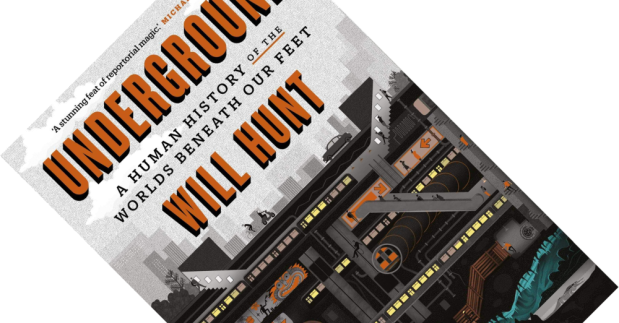

“Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet“, written by Will Hunt, published in Europe by Simon & Schuster in January 2019 (hardback, 277 pages)

It starts off innocently enough, with Hunt discovering an abandoned train tunnel running beneath his home in Providence, Rhode Island. This left in an indelible impression that would be reawakened when he moved to New York City and became part of the city’s urban explorer crowd. From here, Underground follows Hunt on trips around the world, exploring the Parisian catacombs, a sacred Aboriginal ochre mine in outback Australia, the underground cities of Turkey, and the Mexican tunnel systems that became such an intimate part of late Mayan culture.

Hunt weaves history throughout his tales. From the prevalence of the underworld in the gods and places of Greek mythology to the Magdalenian culture, “the Rennaissance Florentines of the Paleolithic Age”, who littered European caves with carved statues and wall paintings between 17,000 to 12,000 years ago. He introduces an extraordinary cast of historical characters, from the 19th-century Parisian cataphile Nadar, who was a very early tinkerer in subterranean photography, to the first attempts at underground mapping by Edouard-Alfred Martel, whose cartographic conventions we still use.

“The modern West may be a secular society now, but go underground, Hunt observes, and “we perform an unwitting shadow-performance of the old rituals […]””

Another very prominent aspect of Hunt’s story is the religious and spiritual pull these places have always had (see also Sacred Darkness: A Global Perspective on the Ritual Use of Caves). Examples he gives include the worshipping of the underground deity El Tío by Bolivian miners, the ritualized Aboriginal pilgrimages to dig up ochre, or the many shamans and philosophers who retreated underground for vision quests and extended retreats. The modern West may be a secular society now, but go underground, Hunt observes, and “we perform an unwitting shadow-performance of the old rituals, sometimes following the ancient choreography down to the last gesture” as we have to twist and contort our bodies in the same way to descend into these spaces.

As Hunt points out, subterranean creation myths are prevalent in cultures around the world. One could even argue that scientists have their own version of this. He joins a team of microbiologists working for the NASA Astrobiologist Institute Life Underground who hunt for so-called “intraterrestrials”, the microbes living deep underground, possibly even throughout Earth’s crust in microscopic passageways (see Deep Life: The Hunt for the Hidden Biology of Earth, Mars, and Beyond for much more on this). And he shortly considers the deep evolutionary history of burrowing animals, writing of ants in particular (see my review of The Evolution Underground: Burrows, Bunkers, and the Marvelous Subterranean World Beneath Our Feet for more on that). Hunt also considers the neurobiological basis to the powerful experience of being underground, illustrating it with his own tales of the disorientation when getting lost in catacombs, or the hallucinations that accompany the sensory deprivation when he camps underground in the dark for twenty-four hours.

“Hunt joins microbiologists […] who hunt for so-called “intraterrestrials”, the microbes living […] throughout Earth’s crust”

Part of what makes Underground such a fascinating book to read is the exclusive access it gives the reader. Over the years, Hunt has become increasingly well-connected in the world of urban explorers, anthropologists, and archaeologists. He meets one of New York’s most elusive and secretive graffiti artists, considered a phantom by the photographer who followed his work for over two decades but never met him. And he gets up close to an exceptional palaeolithic sculpture in the privately owned and zealously guarded Le Tuc cave in the Pyrenees, which archaeologists consider the most inaccessible major decorated cave in Europe.

Hunt has placed his narrative front and centre in this book, forgoing footnotes or an index (though major works are referenced in the text), but adding many fascinating though uncaptioned archival photos throughout. I became so engrossed in the book that I managed to blitz through its 260 pages in between the gaps of a single working day. This is an absolutely mesmerizing book.

So, how does Hunt’s Underground compare to Macfarlane’s Underland? It feels Macfarlane casts his mind outwards more, pondering deep time and the Anthropocene, while Hunt turns his gaze inwards, probing the more human side: religion, spirituality, and neurobiology. Macfarlane, as a nature writer, is more poetic in his writing, though Hunt, using a different tone, is an equally masterful storyteller. Underland is carefully annotated and referenced, but barely illustrated – Underground is the reverse. And even though both writers end up exploring under Paris and both touch on topics of biology and archaeology, it is striking how little they overlap. Clearly, the world under our feet is so vast there is space for more than one book. So why pick one? I heartily recommend them both!

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

, hardback, ebook or audiobook

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

2 comments