8-minute read

keywords: evolutionary biology, history of science

Having just reviewed James T. Costa’s biography of Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, I was keen to read more about one of the most remarkable episodes in the history of science: how two scholars independently hit on the same idea (evolution by natural selection) and how history has largely forgotten one of them. An important piece of evidence to support this claim is one of several notebooks that Wallace kept during his journeys. In On the Organic Law of Change, Costa unlocks this little gem for a broad audience by providing a facsimile, transcription, and a mountain of annotations to place this work in its historical context. You are getting a two-for-one, as I am reviewing this book simultaneously with its companion book Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species, a book I have long been meaning to read.

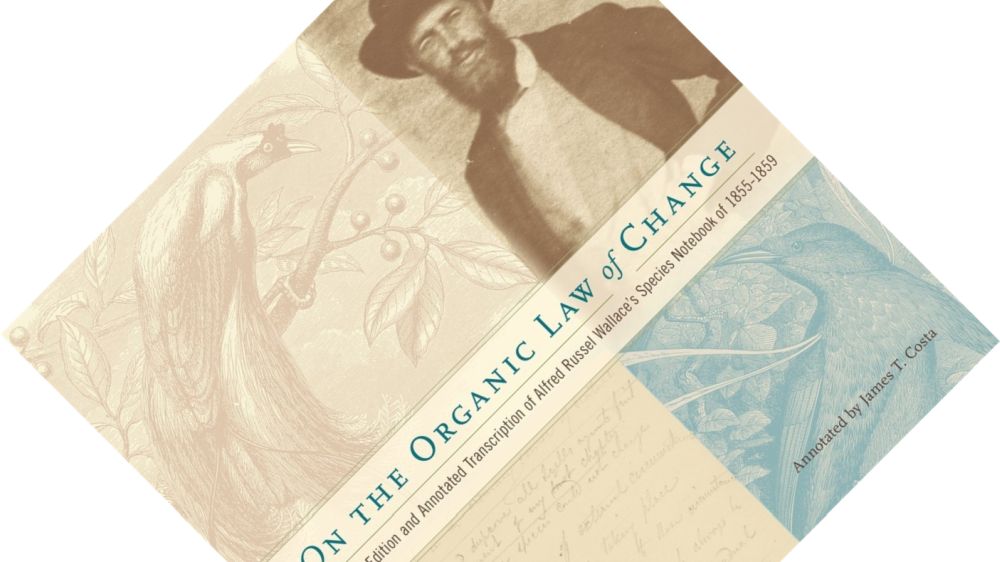

On the Organic Law of Change: A Facsimile Edition and Annotated Transcription of Alfred Russel Wallace’s Species Notebook of 1855-1859, written by Alfred Russel Wallace, annotated by James T. Costa, published by Harvard University Press in November 2013 (hardback, 573 pages)

During his eight-year (1854–1862) collection trip around the Malay Archipelago, Wallace kept a number of notebooks in which he recorded data, observations, and musings. Those that survived have ended up in the library and archives of the Linnean Society in London. In 2010, Costa learned of this particular notebook, dubbed the Species Notebook, from a paper by historian H. Lewis McKinney that he was reading while en route to, no less, the Linnean! In case the dictionary definition of serendipity needed updating, I have a candidate… Upon consulting the Species Notebook, Costa was both enthused by its contents and baffled by its near-anonymity, known only to a small circle of historians. Thus was born the plan to publish it as an annotated transcription, which happened in 2013, the centenary year of Wallace’s death in 1913.

At this point, you may wonder what is so special about this notebook. Well, it contains the seeds for a book Wallace was planning to write on natural selection, an Origin before the On the Origin of Species, if you will. An 1858 letter to Henry Walter Bates similarly mentions plans for an extensive work. In Radical by Nature, Costa was rightfully excited about this: “How fascinating it would have been to have not one but two founding books of evolutionary biology” (p. 246 therein). But it was not to be. Upon learning that Darwin was already far ahead with his book, and still in the middle of his expeditions, Wallace seems to have abandoned this plan. Especially after he received a copy of Darwin’s Origin in 1860 and was very impressed with it, he “evidently felt no need to come out with his own book-length statement on the subject” (p. 8). McKinney suggested that Wallace would have named his book On the Organic Law of Change and to honour McKinney and Wallace’s work, Costa has adopted this title here, realizing in spirit the project that Wallace never finished.

Before delving into the contents, let me get a few technicalities out of the way. The original notebook measures 11 × 17.8 cm and is here reproduced in black-and-white facsimile at 8.5 × 13.7 cm or 77% of the original size. Right next to the facsimile you will find the transcription which retains Wallace’s original spelling and uses several typographical conventions to accurately render the text, including strikethroughs for deletions and sub- and superscripts for insertions. On the opposite page, you will find Costa’s annotations, linked to the transcription by superscripted numbers. To fit facsimile and transcription onto one page, the book is square (measuring 22.9 × 22.9 cm), chunky (573 pages), and (frankly) gorgeous. Wallace used his notebooks tête-bêche, that is, writing towards the middle from both sides, effectively using each notebook for two different purposes. Costa here first reproduces the longer recto side that Wallace labelled “Notes Vertebrata”, followed by the shorter verso side labelled “Notes. Insects. 4”. Blank pages have been omitted. My first impression was: “Ye gods, 18th-century handwriting!”; you will be very glad to have a transcription. This is also the point to acknowledge a few others. Michael Pearson had already transcribed the recto part ten years earlier, providing a useful starting point, while student Anita Murrell did a partial second transcription of the recto notebook which Costa completed. Leslie Costa edited this and generated a complete transcription of the verso side.

“[The Species Notebook] contains the seeds for a book Wallace was planning to write on natural selection, an Origin before the On the Origin of Species.”

Technicalities covered, what is actually in this book? The entries are roughly chronological and contain a potpourri of notes, practicalities, observations, and narrative entries. The verso side, especially, stands out for sketches and the insertion of beetle wings, as well as tables tallying daily catches of insects on different islands. There are comments here on books and papers Wallace had read, musings on how best to organise and label his collections upon return to England, and ethnographic notes on some of the people he encountered. There are natural history observations on birds of paradise and, rather painful to modern readers as Costa warns, graphic descriptions of Wallace hunting orang-utans that often fled, wounded, before succumbing to their gunshot injuries. It is a reminder that terms such as “specimens” and “natural history collections” mask the fact that this involved killing animals.

Costa’s annotations are a vital accompaniment to the transcription. Next to highlighting where place and species names have since changed, he provides mountains of context. What do we know today about certain subjects? Who were the other scholars Wallace mentions and what did they do? Where was Wallace prescient in his ideas and where was he mistaken? Where do we see that he later changed his mind on certain subjects? How did these notes later find their way into his publications? Especially on this last point, Costa quotes from numerous books and papers that Wallace would later write, tracing how his observations on this journey influenced his later thinking.

The meat of this book, however, are the several longer narrative sections on e.g. the fossil record, nest-building behaviour in birds (something that also interested Darwin), instinct in humans and animals, and ice ages. The entries that are really of interest to us are where Wallace builds a case against geologist Charles Lyell. This is such a significant section that it is analysed more in-depth in an 8-page appendix.

“[The Species Notebook contains] a potpourri of notes, practicalities, observations, and narrative entries. […] Costa’s annotations are a vital accompaniment to the transcription, [providing] mountains of context.”

Lyell’s religious convictions got in the way of him accepting transmutation (as evolution was then called) and he was so influential that his word was pretty much law. Even so, he opposed biblical explanations of catastrophic floods and was known for his so-called uniformitarian approach to geology: the planet had been gradually shaped by natural causes still in operation. On this point, Wallace in effect out-Lyelled Lyell. If this is how the inorganic world changes, it is “most unphilosophical” (p. 98) of Lyell to invoke special acts of creation to explain new species. And rather than completely new and different creatures repopulating changed environments, Wallace argued that it would be far more logical that new flora and fauna would be modified versions of previously existing forms.

When it came to domesticated species, Lyell asserted that there is a limit to change since they never transmute into new species and will revert to their wild ancestor if left alone (considered a questionable assumption today). You see Wallace explode off the page with a “Wait, what?” response. He argued that there is no evidence of such limits, and outlined a scenario where varieties beget new varieties beget… etc. Though he would later change his mind on the importance of domestic varieties, here he still argued that they are evidence of transmutation. Particularly interesting are Wallace’s thoughts on the fossil record. Most scholars (except Lyell) agreed that it showed patterns of directional change, but Wallace thought it also showed patterns of descent with modification. Still captured by ideas of linear rankings of organisms, people were confused by the purported contradictions that fossils presented. Not so, argued Wallace, these contradictions only arose from the assumption that the highest forms of one group all had to appear before the lowest forms of the succeeding group did. Wallace instead pictured a branching pattern where each group continued developing after another group had branched off.

All this sounds both familiar and modern, and the contents of the notebook show Wallace’s mind at work, connecting dots. But, taking a step back, how does it all fit into the bigger picture, and where does it clash or agree with Darwin’s ideas? I am going to rather rudely stop you here and refer you to my next review of Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species where I will continue this topic and conclude my review of these two books.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

2 comments