10-minute read

keywords: anthropology, archeology, history

Every few years, it seems, there is a new bestselling Big History book. And not infrequently, they have rather grandiose titles. Who does not remember Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years or Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind? But equally often, these books rapidly show their age and are criticized for oversimplifying matters. And so I found myself with The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, a 692-page brick with an equally grandiose title. In what follows, I hope to convince you why I think this book will stand the test of time better.

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, written by David Graeber and David Wengrow, published in Europe by Allen Lane in October 2021 (hardback, 692 pages)

I see two important reasons. First, rather than one author’s pet theory, The Dawn of Everything is the brainchild of two outspoken writers: anthropologist David Graeber (a figurehead in the Occupy Wall Street movement and author of e.g. Bullshit Jobs) and archaeologist David Wengrow (author of e.g. What Makes Civilization?). I expect a large part of their decade-long collaboration consisted of shooting holes in each other’s arguments. More importantly, rather than yet another history book telling you how humanity got here, they take their respective disciplines to task for dealing in myths. The authors want historians to ask different and better questions, and they critically examine the many assumptions that underlie popular narratives of human history. In this, they succeed spectacularly, and this thought-provoking book is armed to the teeth with fascinating ideas and interpretations that go against mainstream thinking. As usual, I can only touch on some of the larger themes here.

The authors start by tracing the origins of our ideas about human history to the indigenous critique of European civilization. Sorry, the what? Perhaps old hat to seasoned readers of history books, this was one of those intriguing angles on history that was new to a lay reader such as myself. See, Europe was historically a minor player on the world stage and many non-Europeans considered it “an obscure and uninviting backwater full of religious fanatics who […] were largely irrelevant to global trade and world politics” (p. 29). Colonisation exposed us to new ideas that shocked and confused us. Graeber & Wengrow focus on the French coming into contact with Native Americans in Canada, and in particular on Wendat Confederacy philosopher–statesman Kandiaronk as an example of European traders, missionaries, and intellectuals debating with, and being criticized by indigenous people. Historians have downplayed how much these encounters shaped Enlightenment ideas. More importantly, it led to an explicitly racist backlash that saw indigenous people as the lowest rung on the ladder of progress. Its legacy, shaped via several iterations, is the modern textbook narrative: hunter-gathering was replaced by pastoralism and then farming; the agricultural revolution resulted in larger populations producing material surpluses; these allowed for specialist occupations but also needed bureaucracies to share and administer them to everyone; and this top-down control led to today’s nation states. Ta-daa! Except, the authors point out, this simplistic tale of progress ignores and downplays that there was nothing linear or inevitable about where we have ended up.

“The authors want historians to ask different and better questions, and they critically examine the many assumptions that underlie popular narratives of human history.”

Take agriculture. Rather than humans enthusiastically entering into what Harari in Sapiens called a Faustian bargain with crops, there were many pathways and responses. In Neolithic Central Europe, invading farmers went through demographic boom-bust cycles that ultimately approached a regional collapse, rather than a continuous expansion. In the Amazon, people tended to what effectively could be called jungle gardens that Europeans did not even recognize for what they were, leading to the myth of jungles as pristine areas untouched by human hands. In the Fertile Crescent of Mesopotamia, people practised the labour-light variant of flood-retreat agriculture on seasonally flooded wetlands, while hunting and foraging at other times. Experiments show that plant domestication could have been achieved in as little as 20–30 years, so the fact that cereal domestication here took some 3,000 years questions the notion of an agricultural “revolution”. Lastly, this book includes many examples of areas where agriculture was purposefully rejected. Designating such times and places as “pre-agricultural” is misleading, write the authors, they were anti-agricultural.

The idea that agriculture led to large states similarly needs revision. Admittedly, these early conclusions were understandable: past archaeologists focused on areas where the domestication of plants and animals was later followed by the rise of large, politically centralized societies. But correlation is not causation, and some 15–20 additional centres of domestication have since been identified that followed different paths. Some cities have previously remained hidden in the sediments of ancient river deltas until revealed by modern remote-sensing technology. Their combination of flood-retreat agriculture, fishing, and a steady supply of organic construction materials such as mud and reed even suggests that “extensive agriculture may thus have been an outcome, not a cause, of urbanization” (p. 287). And cities did not automatically imply social stratification. The Dawn of Everything fascinates with its numerous examples of large settlements without ruling classes, such as Ukrainian mega-sites, the Harappan civilization, or Mexican city-states. These instead relied on collective decision-making through assemblies or councils, which questions some of the assumptions of evolutionary psychology about scale: that larger human groups require complex (i.e. hierarchical) systems to organize them.

“the indigenous critique of European civilization […] led to an explicitly racist backlash that saw indigenous people as the lowest rung on the ladder of progress. Its legacy […] is the modern textbook narrative.”

A unifying theme in these and other topics is that, according to Graeber & Wengrow, historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists seem to wilfully ignore what is staring them in the face (and this is one of the most important messages of this book): humans have always been very capable of consciously experimenting with different social arrangements. And—this is rarely acknowledged—they did so on a seasonal basis, spending e.g. part of the year settled in large communal groups under a leader, and another part as small, independently roving bands. The archaeological record is understandably biased to stuff that is easily preserved, but more careful excavation methodology and new technologies such as LiDAR and ancient DNA reveal a past that is far more varied than we have allowed for. There is more to history than the rise and fall of empires. Throughout, Graeber & Wengrow convincingly argue that the only thing we can say about our ancestors is that “there is no single pattern. The only consistent phenomenon is the very fact of alteration […] If human beings, through most of our history, have moved back and forth fluidly between different social arrangements […] maybe the real question should be ‘how did we get stuck?'” (p. 115). A good answer to that question is not forthcoming, however, and if the final chapter in their book attempts to answer it, it was a bit of a muddle to me.

Next to criticism, the authors put out some interesting ideas of their own, of which I want to quickly highlight two. The first is that some of the observed variations in social arrangements resulted from schismogenesis. Anthropologist Gregory Bateson coined this term in the 1930s to describe how people define themselves against or in opposition to others, adopting behaviours and attitudes that are different. Graeber & Wengrow here extend this from individuals to whole societies, giving numerous examples. The second idea is that states can be described in terms of three elementary forms of domination: control of violence, control of information, and individual charisma, which express themselves as sovereignty, administration, and competitive politics. Our current states combine these three, and thus we have state-endorsed violence in the form of law enforcement and armies, bureaucracy, and the popularity contests we call elections in some countries, and monarchs, oligarchs, or tyrants in other countries. But looking at history, there is no reason why this should be and the authors provide examples of societies that showed only one or two such forms of control. Asking which past society most resembles today’s is the wrong question to ask. It risks slipping into an exercise in retrofitting, “which makes us scour the ancient world for embryonic versions of our modern nation states” (p. 382).

“A unifying theme [is that] humans have always been very capable of consciously experimenting with different social arrangements. And—this is rarely acknowledged—they did so on a seasonal basis […]”

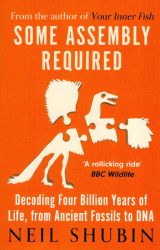

As a final note, part of the reason why this book resonated so much with me is that, as an evolutionary biologist, is see many parallels with discussions in my field. Where Graeber & Wengrow take issue with the teleological trap many historians fall into (only focusing on the outcome of history while skipping over what happened in between), biologists still have to fight the idea that humans are the pinnacle of evolution. Where they object to the constant use of prefixes such as “pre-” and “proto-“, implying that centuries of human development were not “proper” history, I see parallels with what Panciroli and Brusatte have written about “archaic” mammal groups that went extinct: these were not failures or evolutionary dead-ends but were very well-adapted to their environment during their lifetimes, thank-you-very-much. Where they question anthropologists taking today’s remaining hunter-gatherers as valid proxies for how our ancestors lived, primatologists still have to remind us that today’s chimpanzees are not our ancestors but evolved alongside us. And when they point out how e.g. the basic principles of agriculture were known long before they were applied systematically, this sounds like the historical equivalent of Neil Shubin’s argument that “biological innovations never come about during the great transitions they are associated with“. All this should come as no surprise; palaeontology and evolutionary biology are also historical disciplines and, the authors add, Darwin’s ideas influenced social theories about human history.

The Dawn of Everything is a huge and sprawling bombshell of a book. I have left unmentioned several other topics: the overlooked role of women, the legacy of Rousseau’s and Hobbes’s ideas, the origins of inequality and the flawed assumptions hiding behind that question… the book is admittedly a tad long in places and yet the writing is clear and accessible. There are so many historical details and delights hiding between these covers that I was thoroughly enthralled. It is tragic that Graeber passed away in September 2020 before the book was published. As Wengrow writes in his foreword, they had plans for three sequels, covering parts of the world they decided to omit here such as Africa, Australia, and the Pacific. If you have any interest in big history, archaeology, or anthropology, this book is indispensable. I am confident that the questions and critiques raised here will remain relevant for a long time to come.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Postscript: Thanks to the various readers who have commented since this review went live and linked me to critical reviews of this book. Other than the links in the comments section below, I was particularly impressed by the in-depth critique by worbsintowords on his YouTube channel What is Politics? of (so far) five videos (if you have six hours to burn…). If you got the feeling my review overlooked some things, having watched his videos it seems there are some critical questions I did not consider. Will this book stand the test of time better than other big history books, as I wrote in the beginning? I am curious to see Wengrow’s response to the various critiques.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

There’s indeed lots of interesting questions and thought provoking stuff here, but there were just too much troubling signals surrounding this book’s methodology/treatment of sources for me to continue reading it, as I’m not in the mood to second guess everything the authors claim as fact. I’m sure there is much to learn about archeology in the book, but as social science / evolutionary ecology it seems muddled at best.

See:

https://www.persuasion.community/p/a-flawed-history-of-humanity (Admittedly that text also makes a mistake viz. Steckley, see the comments.)

&

http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/12/22/chris-knight-wrong-about-almost-everything/

& Appiah’s reply to Graeber’s reply to his original critique:

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2022/01/13/the-roots-of-inequality-an-exchange/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, it’ll be interesting to read professional responses and see what I have missed or am just not knowledgeable enough about.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing the links, I was also rather skeptical of the authors’ presentation of evidence and “methodology”, despite all the interesting stuff along the way. I’ve been speeding through the book after about half of it just to sample the areas covered and don’t bother too much with the authors’ arguments/proofs supporting the factfulness of their views.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe this is the most important book I have ever read. It is at least as important as many others. It’s a must read for historians, anthropologists, archeologists, and other -ologists.

Frankly it was a surprising read and very refreshing.

LikeLike