8-minute read

keywords: geology, history of science, paleontology

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are probably one of London’s better-kept secrets. This unlikely collection of life-size outdoor sculptures of some 30 prehistoric creatures—including dinosaurs, marine reptiles, and extinct mammals—has survived in the city’s southeast for almost 170 years. They have been lampooned for being terribly outdated in light of what we know today. But that does them no justice. In this gorgeously illustrated book, palaeontologist and palaeoartist Mark Witton has teamed up with Ellinor Michel, an evolutionary biologist and chair and co-founder of the Friends of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs charity. Together, they chart the full story of the inception, planning, construction, reception, and survival of the sculptures. Foremost, it shows how cutting-edge they were back then, why they still matter today, and why they need our help.

The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, written by Mark P. Witton and Ellinor Michel, published by Crowood Press in May 2022 (hardback, 192 pages)

Dating back to 1854, the sculptures are some of the last remnants of the Crystal Palace Park. The Crystal Palace was a stupendously large cast iron and plate glass building that was a much larger rebuild of the already ostentatious Great Exhibition of 1851 in London’s Hyde Park. Its mission: to educate the general public in the art, science, culture, and technology of the day in a leisurely park setting with statues, gardens, and enormous fountains. After introducing this Victorian extravaganza, Witton & Michel discuss the various people involved in realizing the Geological Court in the southern part of the park, including foremost creature designer and sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and anatomist and palaeontologist Richard Owen who was to be the palaeontological consultant. As explained here, several historians have shown that Owen was really not all that interested or involved in the consulting job and even subtly criticized some of Hawkins’s design decisions in his 1854 guide to the Geological Court.

Witton & Michel furthermore introduce what is probably the court’s most-overlooked and least-appreciated aspect: the Geological Illustrations. The animal sculptures were placed in a landscape containing artificial rock outcrops of corresponding geological ages, leading visitors on a journey through time. Many tonnes of original rock of the right ages were sourced all over Britain for this, showing the incredible attention to detail. Unfortunately, the lack of historical documentation and interest in this feature has meant that quite a bit of it has disappeared over the years. Much of our current understanding was achieved retrospectively, and this book in part relies on modern research by geologist Peter Doyle.

Witton & Michel furthermore introduce what is probably the court’s most-overlooked and least-appreciated aspect: the Geological Illustrations. The animal sculptures were placed in a landscape containing artificial rock outcrops of corresponding geological ages, leading visitors on a journey through time. Many tonnes of original rock of the right ages were sourced all over Britain for this, showing the incredible attention to detail. Unfortunately, the lack of historical documentation and interest in this feature has meant that quite a bit of it has disappeared over the years. Much of our current understanding was achieved retrospectively, and this book in part relies on modern research by geologist Peter Doyle.

Finally, they go into the construction and engineering of the sculptures, of which we know relatively little. Some of this was still ongoing when the park opened in 1854, and Hawkins’s workshop was used as a marketing tool towards visiting reporters. At the time, the press reported a list of ingredients for one of the Iguanodon sculptures, but, as the authors explain, notebooks and business records that might have contained such details were not kept for posterity. Much has been revealed by later restoration work. Next to period photos and illustrations, the authors include modern photos and diagrams that reveal new details or best guesses not previously discussed elsewhere. Moved or missing sculptures are also discussed in detail, including the revelation here that one Megaloceros fawn is more likely the only surviving sculpture of a group of four ‘Anoplotherium gracile‘ (today classified as Xiphodon gracilis) that have gone missing over the years.

“[the authors] highlight how much Hawkins achieved with the sometimes limited information available at the time, and how much realism and life he breathed into his sculptures”

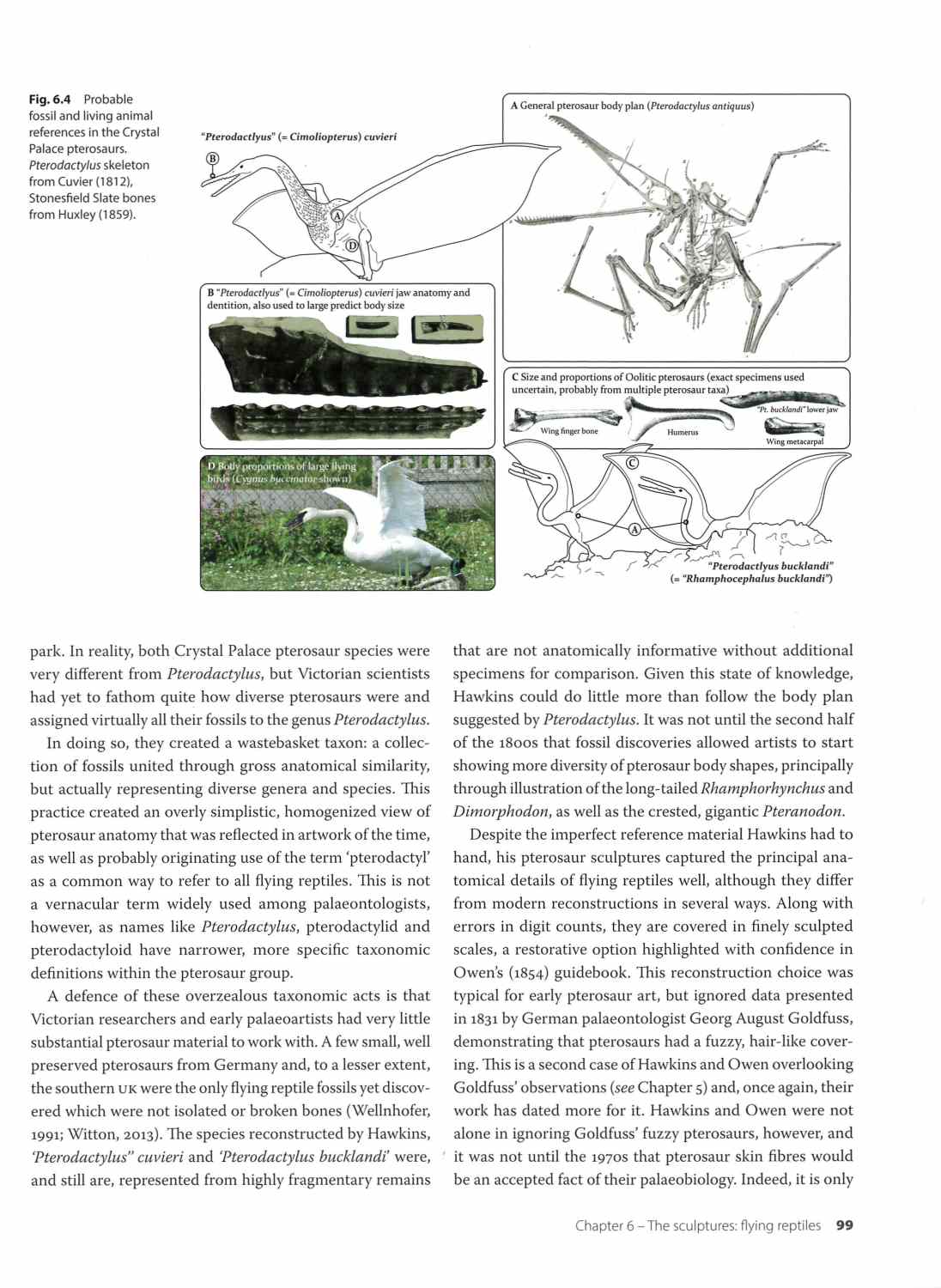

The real meat of the book is the middle section which covers the animal sculptures in an unprecedented level of detail. This is really where Witton’s palaeontological background shines and he can nerd out to his heart’s delight. There is discussion of the fossil material and living species likely used as guides to flesh out details, with innovative diagrams linking this to the various anatomical regions of each sculpture. There is extensive discussion on what species are represented and whether they are still valid today (e.g. the theropod dinosaur Megalosaurus bucklandii), have since changed name (e.g. ‘Plesiosaurus hawkinsii‘ that now goes by the awesome-sounding name Thalassiodracon hawkinsii), or really are chimaeras (e.g. the three frog-like creatures called ‘Labyrinthodon‘ that in hindsight are “a fictional animal: a chimera of temnospondyl and reptile remains that bore little resemblance to any one of its constituent species” [p. 143]). The level of detail here will satisfy even professional palaeontologists, though I can see some of the finer points perhaps being a bit technical for a general audience.

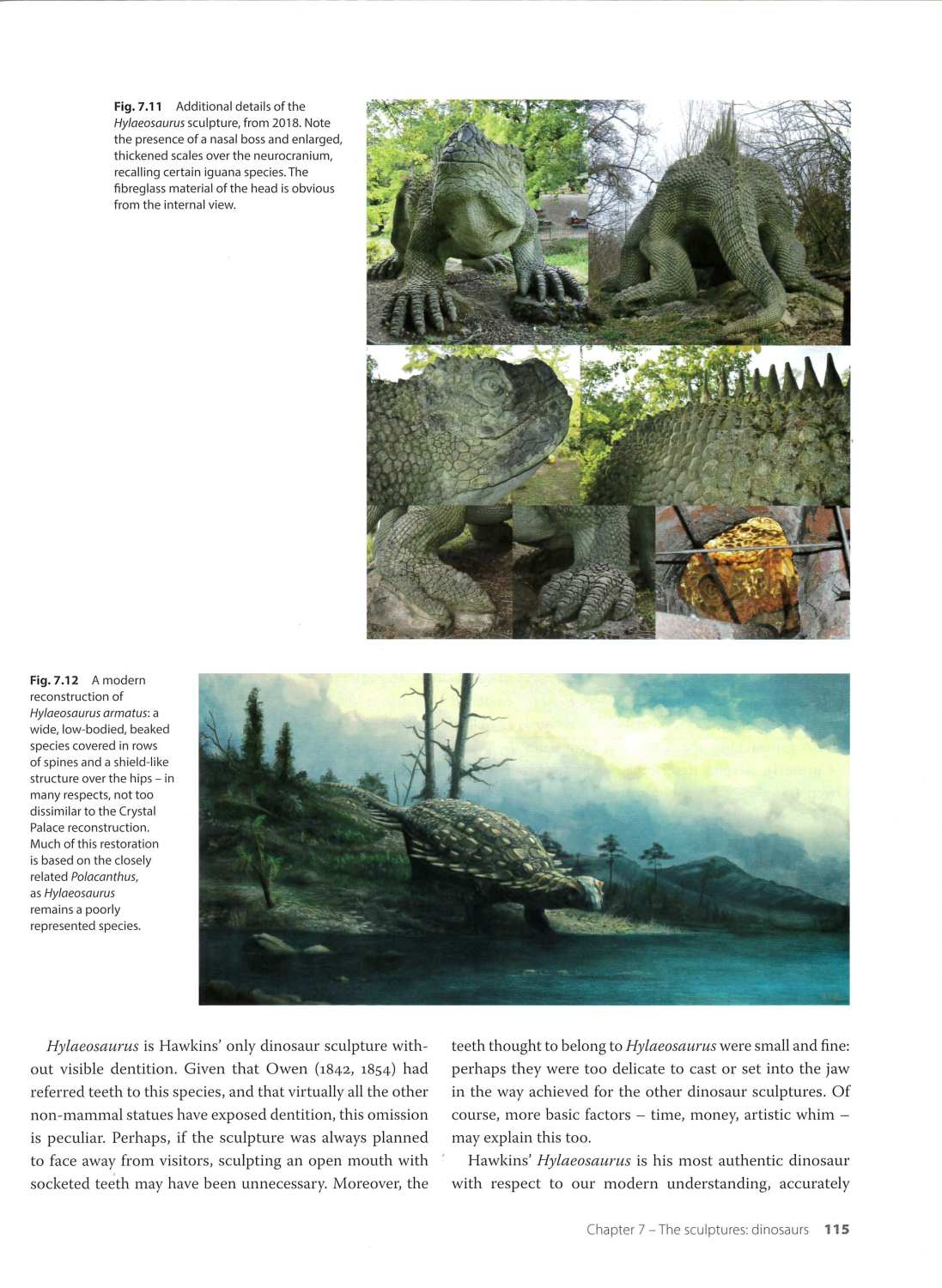

The sculptures are a tangible example of the self-correcting nature of science and the authors discuss how our understanding of these creatures has since advanced and how they are depicted today, with Witton contributing artwork. Unavoidably, Hawkins made mistakes and in some cases, errors came to light very soon, such as Megalosaurus and Iguanodon walking on two rather than four legs. But Witton & Michel also point out the many things that still stand, such as the mammal and ichthyosaur reconstructions. Above all, they highlight how much Hawkins achieved with the sometimes limited information available at the time, and how much realism and life he breathed into his sculptures, evidencing his skill as a natural history artist. The poses, skin and integument details, and their bulk and soft-tissue reconstructions (a topic Witton is particularly keen on) are incredibly life-like, putting to shame many modern attempts. Photomontages of close-up shots reveal numerous details that will be hard to see from a distance or might be obscured by vegetation. My only complaint is that most of these are quite small, with some component photos stamp-sized. I would not have minded a full page dedicated to each montage, though considerations of page count and price will no doubt have limited the authors.

The sculptures are a tangible example of the self-correcting nature of science and the authors discuss how our understanding of these creatures has since advanced and how they are depicted today, with Witton contributing artwork. Unavoidably, Hawkins made mistakes and in some cases, errors came to light very soon, such as Megalosaurus and Iguanodon walking on two rather than four legs. But Witton & Michel also point out the many things that still stand, such as the mammal and ichthyosaur reconstructions. Above all, they highlight how much Hawkins achieved with the sometimes limited information available at the time, and how much realism and life he breathed into his sculptures, evidencing his skill as a natural history artist. The poses, skin and integument details, and their bulk and soft-tissue reconstructions (a topic Witton is particularly keen on) are incredibly life-like, putting to shame many modern attempts. Photomontages of close-up shots reveal numerous details that will be hard to see from a distance or might be obscured by vegetation. My only complaint is that most of these are quite small, with some component photos stamp-sized. I would not have minded a full page dedicated to each montage, though considerations of page count and price will no doubt have limited the authors.

Two final fascinating chapters detail the reception and conservation of the sculptures. The authors document the mixture of positive and negative responses throughout the 19th and 20th centuries and frankly admit that some concerns, e.g. the difficulty of displacing outdated ideas from the public mind, are still true of palaeoart today. Fortunately, especially professional opinion of the sculptures has mellowed over time as the realisation sunk in that “science communicators can do no more than present snapshots of contemporary understanding to the public” (p. 18). The authors refer to Henry Neville Hutchinson’s 1893 book Extinct Monsters as the earliest example of this, and the current book can be seen as continuing that tradition of appreciation and evaluation in an appropriate historical context[1].

“professional opinion of the sculptures has mellowed over time as the realisation sunk in that “science communicators can do no more than present snapshots of contemporary understanding to the public“”

After the Crystal Palace burnt down in 1936, the visitor stream dried up and the park has subsequently seen a race course for cars, a football stadium, and military use during World War II. Possibly their location at the edge of the park has saved the sculptures from simply being bulldozed. Only in 1973 did Historic England include the site on their National Heritage List, upgrading its classification in 2009 and 2020, while the Friends of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs charity was only formed in 2013. Considering all this, it is a miracle that the sculptures are still with us today. As Witton & Michel document, this has been in no small part to generations of caretakers who have looked after them. However, they mince no words pointing out that, more than vandalism, water, weather, or plants,  “custodial indifference and mismanagement […] are probably the single biggest contributor to the loss and damage of Geological Illustrations and palaeontological models” (p. 178). Continued attention and conservation will be required to preserve this site, and the authors are donating their share of the book’s proceeds to the Friends of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs.

“custodial indifference and mismanagement […] are probably the single biggest contributor to the loss and damage of Geological Illustrations and palaeontological models” (p. 178). Continued attention and conservation will be required to preserve this site, and the authors are donating their share of the book’s proceeds to the Friends of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs.

Information on these sculptures has so far been scattered and pretty hard to get by. The only notable previous book is The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, published in 1994 by the Crystal Palace Foundation (and spruced somewhat for its 2019 reprint) which contains a fair number of historic photos not reproduced here. However, the new information and the level of detail, analysis, and knowledge that Witton & Michel bring to the subject, as well as the book’s high production values, now make The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs the go-to book.

In case it is not yet clear, the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are one of those endearing quirks of history I absolutely adore. This site is unique in the world and provides an unparalleled peek into the history of palaeontology and geology. This book has given me a renewed sense of appreciation and I cannot wait to visit the park again[2] next time I am in London.

1. ↑ Palaeontologist Darren Naish also wrote a spirited defence on his blog Tetrapod Zoology in 2016

2. ↑ I first visited the dinosaurs in September 2018 and had the distinct pleasure of joining a guided tour to the islands led by Darren Naish. Mark Witton was also there and quite some of the photos in this book were made during that visit. The Inquisitive Biologist can be found hiding in the background of one of the photos on page 101.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________