9-minute read

keywords: marine biology, wildlife conservation

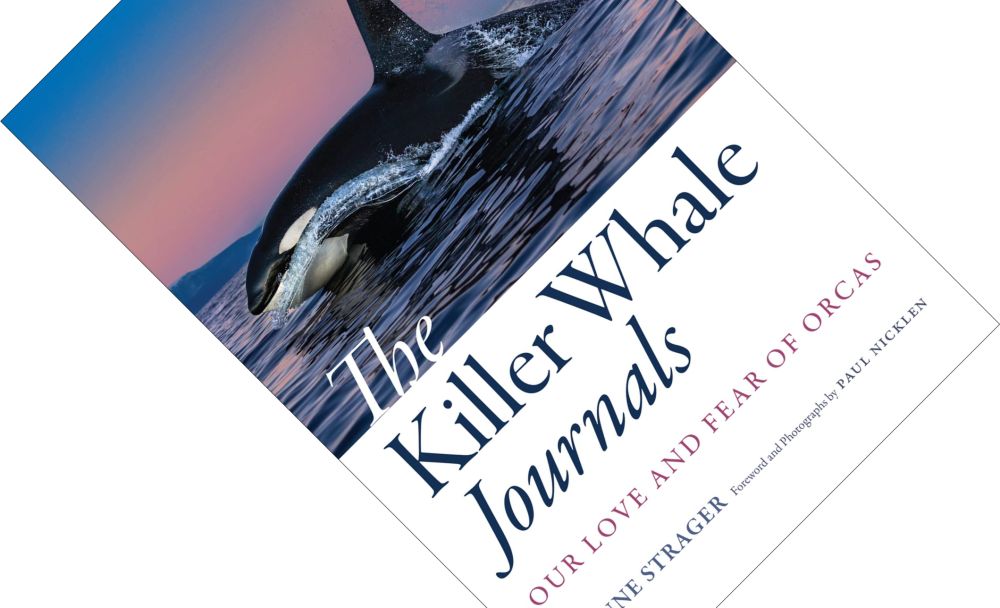

As some of the world’s largest predators, orcas are both loved and loathed, though these sentiments sometimes come from unexpected corners. Danish marine biologist Hanne Strager has studied orcas and other whales for some four decades, working with a wide range of people. In The Killer Whale Journals, she plumbs the complexities and nuances of people’s attitudes, writing a balanced, fair, and thought-provoking insider’s account. Given the preponderance of research and books on Pacific Northwest orcas, hers is a refreshingly cosmopolitan perspective, taking in the experiences of people past and present in many other parts of the world.

The Killer Whale Journals: Our Love and Fear of Orcas, written by Hanne Strager, published by Johns Hopkins University Press in June 2023 (hardback, 266 pages)

Strager’s involvement with whale research started on a whim when she volunteered as a cook on a small research vessel going around the Lofoten Islands in northern Norway. This was in the 1980s and would, with some interruptions, be the start of a career in research and education that lasts to this day. Though she is fully qualified to write a scholarly work on orca[1] biology, this is not that book[2]. Rather, this is “a patchwork of stories I have collected over my years on the ocean about our relationship with the biggest predator on Earth” (p. 17). And what a wide-ranging, multi-hued patchwork it has become!

Some of these relationships are as you would expect. In her early days in Norway, both the whalers and fishermen she spoke to disliked orcas, considering them a pest species that frightens away other whales and eats all the herring. The best she can get out of the whalers, after showing them footage of orcas hunting herring, is admiration, though “it’s the hunters’ admiration for other smart hunters” (p. 61). Similarly expected is the strong respect expressed by First Nations people in British Columbia. She visits Ernest Alfred of the ‘Namgis tribe who lives on a tiny island off Vancouver Island. He quit his job as a park warden in 2018 to spend 284 days occupying a local island in protest against the operations of an open-net fish farm, echoing earlier protests by e.g. whale biologist Alexandra Morton. Large-scale aquaculture of Atlantic salmon off the coast of North America is big business but has well-documented impacts on the local environment and salmon populations that are in turn food for orcas. Alfred’s clever use of social media to broadcast his protest seems to have had an effect, and Canada is now seeking to end open-net fish farming in its waters.

Other people hold attitudes you would not expect, breaking with stereotypes. The Thawa tribe in New South Wales, Australia developed a cross-species cooperation with orcas in Twofold Bay: the orcas drove baleen whales close to the coast making them easier to catch, the hunters in turn left the carcasses in the water for a few days so orcas could take the choice bits. When Scottish whalers emigrated to the area in the mid-1800s, they continued this relationship, leading to an unlikely, century-long alliance between orcas and whalers. At the other end of the spectrum, Strager visits Inuit hunters in Greenland who continue to rely on the sea for their sustenance. They kill orcas on sight, convinced they eat narwhals. However, data from the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources do not back up this assertion: orcas rarely share the waters with narwhals, nor have narwhal remains been found in their stomachs. Hunting organizations disagree and stick to their narrative, continuing to kill orcas even though the meat is unsuitable for human consumption due to high levels of bioaccumulated pollutants. Strager is loathe to judge these people given their hospitality and willingness to talk to her, but she candidly admits that she is left troubled. “It is a widely accepted belief that the Inuit have a special relationship with nature and that this is automatically sustainable. Yet I can’t help but wonder if [this idea] is one of those persistent stereotypes, grounded in traditions and some truths but not totally accurate today” (p. 193). This might be an unpopular thing to say, but it strikes me as a good example of the limits of Indigenous ways of knowing. Yes, science has ignored Indigenous knowledge for too long, but it cannot be exempt from criticism. I rather agree with what Carl Safina recently wrote in Alfie & Me on the difference between the two: “For discerning objective reality […] science has the stronger claim” (p. 36 therein).

“As some of the world’s largest predators, orcas are both loved and loathed, though these sentiments sometimes come from unexpected corners.”

What further contributes to the book’s full-bodied picture is that Strager, as a Danish scientist, provides a non-US-centric perspective and has access to material written in other languages. With the help of a friend, she translates hundreds of newspaper articles from Iceland’s National Archive to puzzle together the story of how the US Air Force got involved in massacring orcas here in the 1950s, doing bombing raids on pods. Fishermen, driven to despair when the orcas discovered a new trick to catch fish from their gill nets, complained to the authorities who asked the Americans for help. Given that the presence of a US Air Force base in Iceland was controversial at the time, it presented a great PR exercise for the military, creating goodwill amongst the locals. Being plugged into the Scandinavian research community, Strager can furthermore draw on her connections to visit and speak to people in Denmark, Greenland, Russia, and various places in Norway.

Increasingly, the demonization of orcas has made way for a different understanding, seeing these as intelligent mammals, not unlike us. A new generation of fishermen in Norway is less hostile. The extra income generated by wildlife tourism and whale watching does not hurt, but, adds a Norwegian marine ecologist, there is also a sense of pride in one’s local patch. Having tourists visit from around the world and witnessing their awe can make people realize that their humdrum backyard is maybe not that humdrum after all. Captive orcas in aquaria and marine parks are another reason why public attitudes shifted from fear to fascination to concern over animal welfare, as has been so carefully documented by James M. Colby in Orca. Despite opposition, the capture and trade of orcas continues and one harrowing chapter delves into the infamous Russian “whale jail” that was exposed by journalist Mashaz Netrebenko in 2018.

As mentioned earlier, this is not a scholarly book, so orca biology takes a bit of a backseat. Nevertheless, you will learn about, for instance, the different orca populations and their dietary specializations, and how they do not mix genetically, causing a headache for conservation biologists. This behaviour is a prominent example of culture in cetaceans as it is learned and passed on from generation to generation. Strager also discusses the recent spate of attacks by orcas on pleasure craft in the Mediterranean. A marine mammal researcher from Madeira admits that she does not know if this is retaliation or just rambunctious play, but its rapid spread in the region sure points to orcas learning new behaviours from each other. Conservation concerns are the main recurrent biological theme in this book. Reflecting on the situation in the Pacific Northwest and the tremendous efforts expended on returning one orphaned orca, Springer, back to its pod, Strager writes how: “saving one orphan whale is a trivial task compared to changing the conditions that threaten these whales” (p. 214). Overfishing, chemical and noise pollution, shipping, aquaculture, hydroelectric dams—the long list of environmental insults is a poignant reminder that, in the words of Michael J. Moore, we are all whalers, even if only indirectly.

“Given the preponderance of research and books on Pacific Northwest orcas, Strager’s perspective is refreshingly cosmopolitan, taking in the experiences of people in many other parts of the world.”

The other aspect that takes a backseat is Strager’s personal story. This book covers some four decades of her life, from a young student in the 1980s to a seasoned researcher now. And yet, important life events are mentioned rather than elaborated upon. They help provide a sense of place and circumstance, but never play a central or even supporting role in her stories. The fact that she would have a child with the man who helped her onto that first research vessel all those years ago is one of those offhand, blink-and-you-miss-it comments. Nor does she mention that she is now working as a Director of Exhibitions, turning the local Whale Center in Andenes, Norway, where she worked for years into a world-class museum, The Whale, to open in 2025.

The Killer Whale Journals takes in an impressively broad range of people past and present. There are various other fascinating stories I have not even touched upon here. Strager remains mild-mannered and non-judgemental throughout as she carefully charts the nuances, inconsistencies, and complexities of people’s attitudes. If you have any interest in cetaceans or marine biology more generally, this absorbing book comes recommended.

1. ↑ Going on a tangent here: Strager, perhaps surprisingly, prefers the name “killer whale”. Partially this is out of habit, partially because the meaning of the species name Orcinus orca is little better. One loose translation is “demon from the underworld”, with Orcinus meaning “of the kingdom of the dead”. However, orca could also refer to the Latin word for cask or barrel, or to a large whale (Wikipedia and Wiktionary disagree with each other; also see this brief and amusing write-up on Whale Tales). Anyway, it is all a bit tomato tomato: I prefer orca and will stick with that here.

2. ↑ Remarkably, there does not seem to be a textbook dedicated to just orca biology. Erich Hoyt’s Orca serves up some of this but with plenty of historical and narrative asides. Readers could start with the broader Whales: Their Biology and Behavior or, if you are particularly adventurous, the Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________