6-minute read

keywords: ecology, ethology, evolutionary biology

Where evolution is concerned, the city is a cauldron exerting its own unique mix of selection pressures on the organisms living here. The metronome beating at the heart of this process is sex. For this book, retired physician Kenneth D. Frank has explored his hometown of Philadelphia in the Eastern US state of Pennsylvania and documented the astonishing variety of sex lives playing out right under our noses. Many of these organisms can be found in cities around the world. Remarkably well-researched and richly illustrated with photos, this collection of 106 one-page vignettes shows what avocational naturalists can contribute both in terms of observations and in terms of highlighting the many basic questions that are still unanswered.

Sex in City Plants, Animals, Fungi, and More: A Guide to Reproductive Diversity, written by Kenneth D. Frank, published by Columbia University Press in May 2022 (paperback, 175 pages)

That animals get up to all sorts of reproductive shenanigans is something I would know. I spent five years for my PhD degree looking at the sex life of a small fish, the three-spined stickleback, and especially how males have different options when it comes to siring offspring, known as alternative reproductive tactics. Frank, however, opens the book with some 30-odd vignettes on plants, reminding me that I really do not appreciate plants enough.

Take purple cliffbrake fern (Pellaea atropurpurea) that does not need to be fertilized by sperm and whose embryos emerge from somatic (i.e. body) cells. Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) can form big showy flowers that are cross-fertilized (i.e. the regular bees-and-flowers story) or it can form smaller flowers that fertilize themselves under conditions of drought and shade. St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum) can do it all: self-fertilization, cross-fertilization, double fertilization[1], single fertilization, or no fertilization. All these species are well adapted for variable conditions in city environments. Meanwhile, a tree such as Norway maple (Acer platanoides) can change its sex over the course of days, producing male flowers followed by female flowers, or vice versa. This prevents self-fertilization, which is a measure of last resort from an evolutionary point of view as it produces offspring that are less genetically diverse.

Take purple cliffbrake fern (Pellaea atropurpurea) that does not need to be fertilized by sperm and whose embryos emerge from somatic (i.e. body) cells. Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) can form big showy flowers that are cross-fertilized (i.e. the regular bees-and-flowers story) or it can form smaller flowers that fertilize themselves under conditions of drought and shade. St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum) can do it all: self-fertilization, cross-fertilization, double fertilization[1], single fertilization, or no fertilization. All these species are well adapted for variable conditions in city environments. Meanwhile, a tree such as Norway maple (Acer platanoides) can change its sex over the course of days, producing male flowers followed by female flowers, or vice versa. This prevents self-fertilization, which is a measure of last resort from an evolutionary point of view as it produces offspring that are less genetically diverse.

“[…] this collection of 106 one-page vignettes shows what avocational naturalists can contribute both in terms of observations and in terms of highlighting the many basic questions that are still unanswered.”

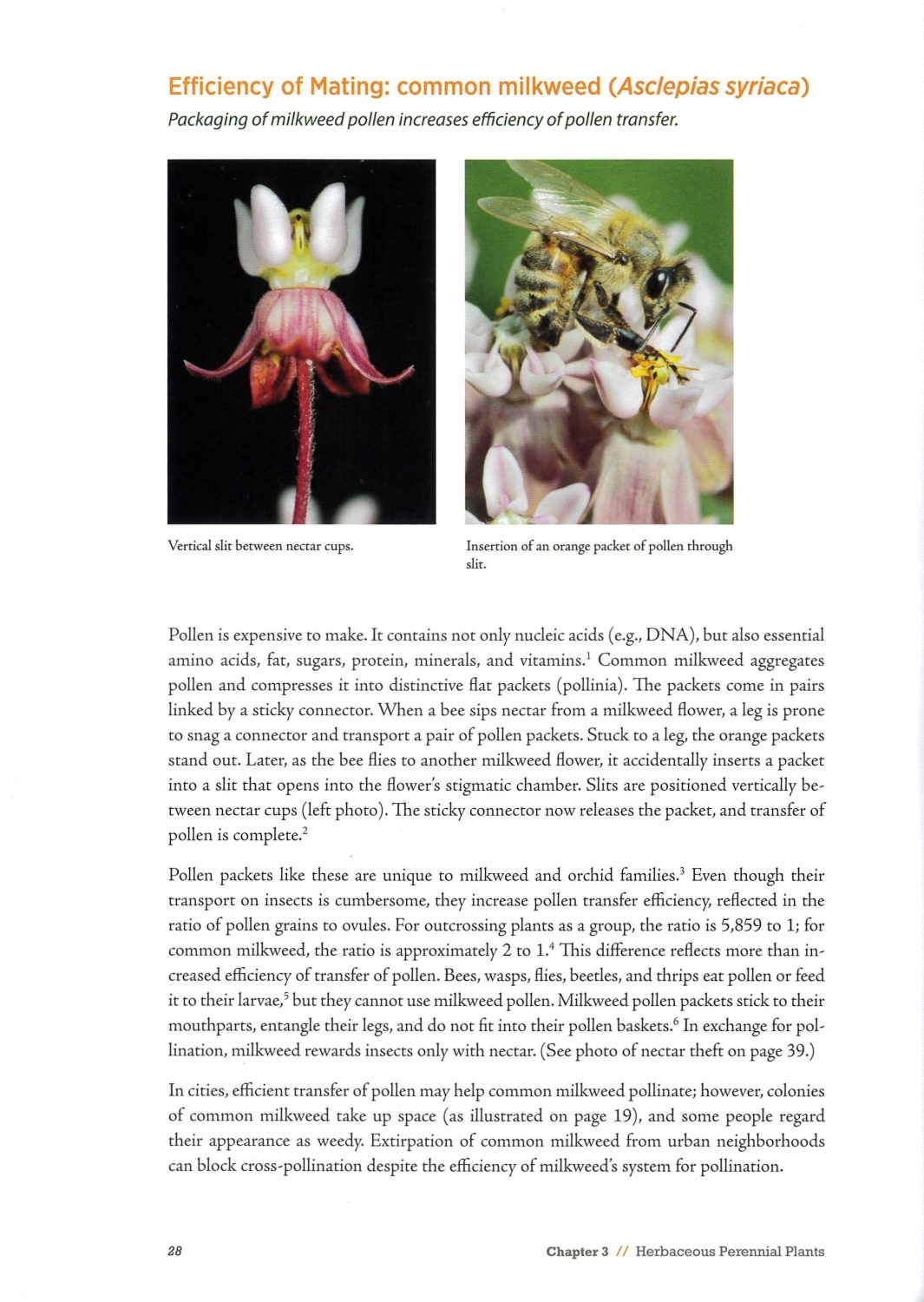

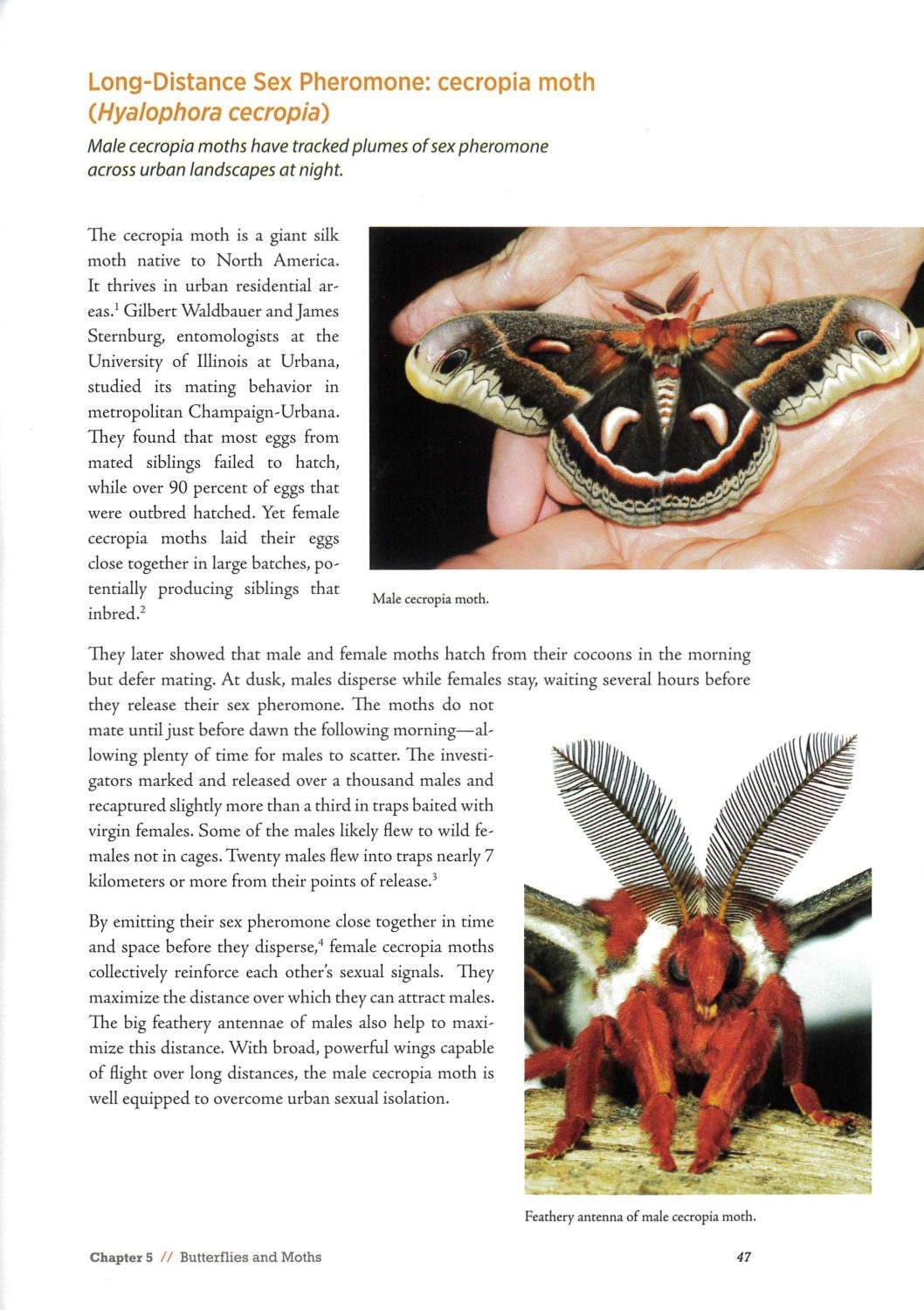

The next major group Frank covers are insects and other invertebrates whose sex lives are just wicked. Male European paper wasps (Polistes dominula) are a lekking species, which means they congregate in a small area, the lek, to collectively advertise their presence in the hope of picking up a female. (One could theoretically argue that nightclubs fulfil a similar function in humans.) Male blue dasher dragonflies (Pachydiplax longipennis) are territorial and defend areas preferred by egg-laying females. The females can mimic the male in appearance and it seems these mimics avoid harassment by males. A problem for both sexes is light reflected by metal and glass, which is polarized—the light waves vibrate predominantly in one direction—and resembles light reflected by water. Some dragonflies end up defending the shiny surface of a car bonnet rather than a pond. Milkweed aphids (Aphis nerrii) are such pests as they reproduce through parthenogenesis: eggs develop into embryos without requiring fertilization, and all grow into females that will never mate. The bridge spider (Larinioides sclopetarius) thrives around outdoor lights, which form hubs where spiders “eat, meet, and mate” (p. 76). Males have secondary genitalia and first transfer their sperm to two so-called pedipalps: pom-pom-like appendages in front of their head that they use to inseminate females with.

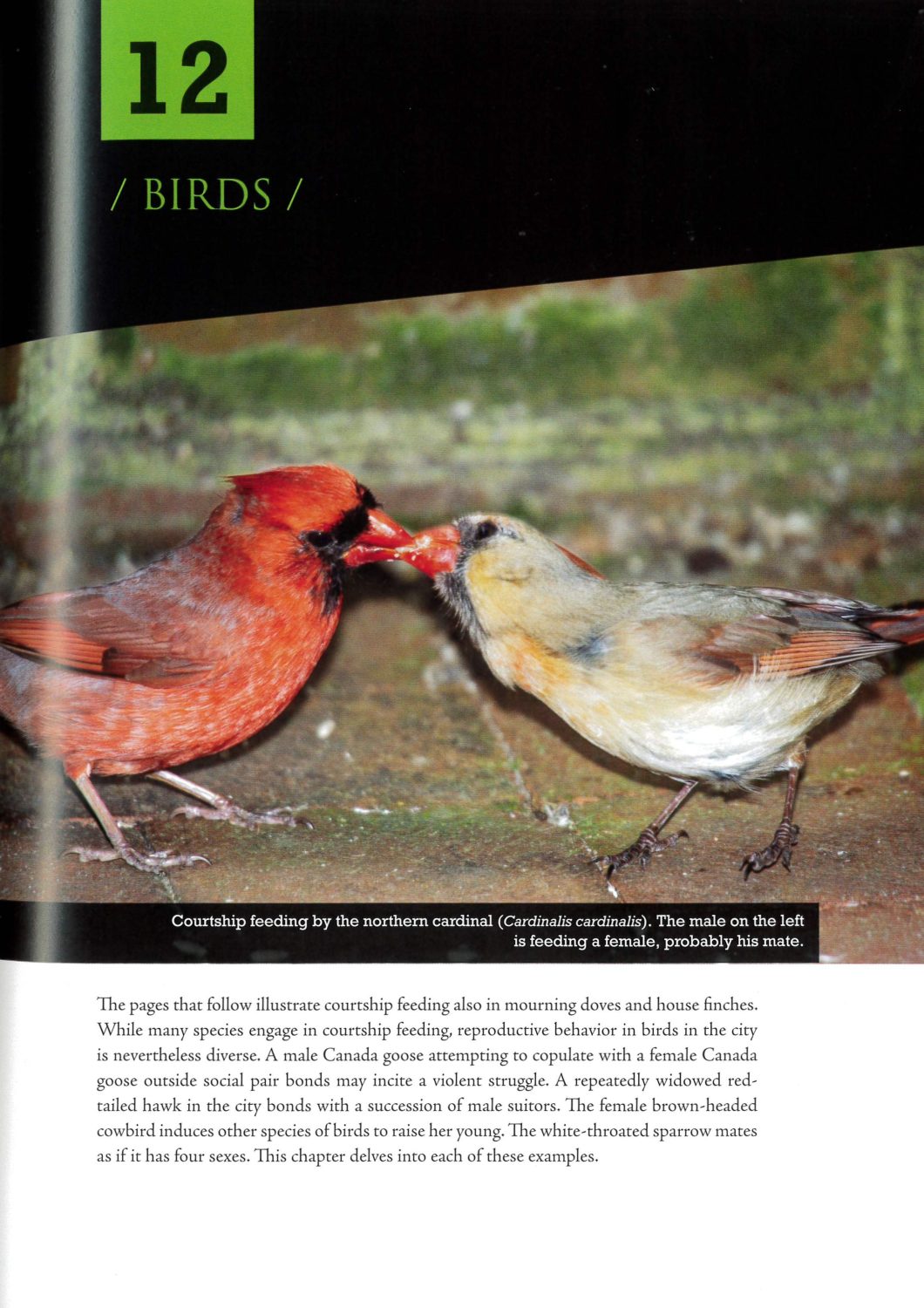

In comparison, vertebrates seem tame. As in many other reptiles, sex in red-eared slider turtles (Trachemys scripta elegans) is temperature-dependent. What I did not know is they simply have no sex chromosomes! Male bluegill fish (Lepomis macrochirus) build nesting areas to which they attract females. Afterwards, they nurse the broods on their own. Some males, sneaker males, forego all this effort and simply intrude on an ongoing mating, releasing their own cloud of sperm in the water (the sticklebacks I studied do the same). Male eastern gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) leave a mating plug in the female’s genital tract which is hypothesized to have one or more functions (including a sperm blocker to other males, a hormone booster, or maybe an anti-aphrodisiac pheromone releaser). European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) are a fine example of a species that is socially but not sexually monogamous, as paternity tests have shown. Notably missing from the book are mammalian predators such as foxes and coyotes that also thrive in city environments.

In comparison, vertebrates seem tame. As in many other reptiles, sex in red-eared slider turtles (Trachemys scripta elegans) is temperature-dependent. What I did not know is they simply have no sex chromosomes! Male bluegill fish (Lepomis macrochirus) build nesting areas to which they attract females. Afterwards, they nurse the broods on their own. Some males, sneaker males, forego all this effort and simply intrude on an ongoing mating, releasing their own cloud of sperm in the water (the sticklebacks I studied do the same). Male eastern gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) leave a mating plug in the female’s genital tract which is hypothesized to have one or more functions (including a sperm blocker to other males, a hormone booster, or maybe an anti-aphrodisiac pheromone releaser). European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) are a fine example of a species that is socially but not sexually monogamous, as paternity tests have shown. Notably missing from the book are mammalian predators such as foxes and coyotes that also thrive in city environments.

“Frank highlights where we know or suspect that certain strategies result in organisms either thriving or struggling in urban environments; not every organism can radically reorganise its sex life to take advantage of the city.”

The above is a small sample from the wide range of reproductive diversity on display in urban environments. Frank highlights where we know or suspect that certain strategies result in organisms either thriving or struggling in urban environments; not every organism can radically reorganise its sex life to take advantage of the city. Obviously, Frank has not observed all these phenomena first-hand, and the amount of research that has gone into this book is impressive. The reference section spans 32 pages, which is a lot considering the vignettes take up only 106 pages. Many include facts and data from five to ten different papers. He also uses this opportunity to highlight how many basic biological questions remain unanswered. For example, does nocturnal light pollution interfere with moths fertilizing flowers of  white campion (Silene latifolia)? How do female dragonflies mimicking males mate and could this be a post-fertilization adaptation? Does artificial crowding in city parks cause male squirrels to become less aggressive over time? What Frank has done is track down nearly all the species discussed here: the book is richly illustrated with his (macro)photography, with some contributions by others.

white campion (Silene latifolia)? How do female dragonflies mimicking males mate and could this be a post-fertilization adaptation? Does artificial crowding in city parks cause male squirrels to become less aggressive over time? What Frank has done is track down nearly all the species discussed here: the book is richly illustrated with his (macro)photography, with some contributions by others.

As much as Sex in City Plants, Animals, Fungi, and More is a nicely curated collection of interesting nuggets, it lacks an overall narrative. In particular, the bigger picture of how reproduction translates into longer-term evolutionary changes is only occasionally hinted at. Menno Schilthuizen wrote a very entertaining account in Darwin Comes to Town, but it has become a serious subfield of evolutionary biology. As such, this is a popular science book that is great for dipping into (whether it would make for suitable bedtime reading depends entirely on what you are into…). And if you are looking for inspiration for student or PhD projects, the book provides numerous ideas of biological mysteries at your doorstep.

1. ↑ double fertilization is the default in flowering plants. One fertilized cell forms the embryo, and the other forms endosperm that offers nutritional support to the developing embryo.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Sex in City Plants, Animals, Fungi, and More

Sex in City Plants, Animals, Fungi, and More

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________