7-minute read

keywords: evolution

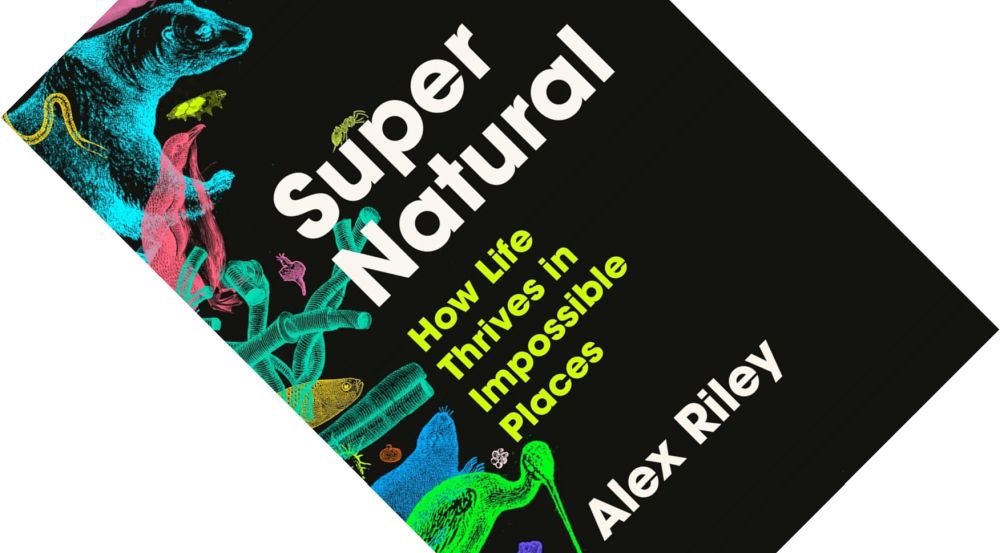

Once it evolved, “life unfurled into every open space and every crevice” (p. 9). This is one of the observations underlying Super Natural, the second book by science writer Alex Riley. In the drive to escape predators and competitors, to find an ecological niche of one’s own, organisms have adapted to some of the planet’s most extreme and hostile environments. Extreme and hostile to humans, that is. In this entertaining romp through life’s outliers, Riley marvels at the resilience and ingenuity of many organisms and introduces you to some of the truly mind-boggling conditions under which they not only survive, but often thrive.

Super Natural: How Life Thrives in Impossible Places, written by Alex Riley, published in Europe by Atlantic Books in June 2025 (hardback, 358 pages)

Super Natural follows the tried-and-tested formula of the author interviewing scores of scientists and often accompanying them in the field or lab to meet their study system. Well-known science communicators such as Ed Yong and Carl Zimmer have used this approach to great effect. Riley fell into this book project almost by accident during the darkest moments of the COVID-19 lockdowns, trying to find hope in nature’s capacity to deal with adversity. From research and initial writing blossomed this book in which he examines how creatures large and small deal with extremes of water, oxygen, food, freezing, pressure, heat, darkness, and radiation.

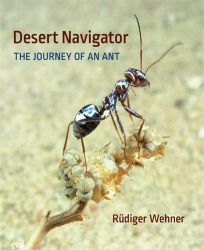

Over the years, I have read or heard about various organisms featured here, though Riley has a knack of powerfully characterising what makes them so special. Desert ants of the genus Cataglyphis are mentioned here, quite rightly, as one of nature’s champions in withstanding extreme heat. While most creatures avoid the hottest part of the day, these ants will not leave their nest until it is blisteringly hot, spending “the next few hours in an inhospitable niche that opens and closes with temperature […] they don’t so much exist in a place as inhabit a period of time” (p. 202). I was also familiar with some of the extremes of food consumption and starvation that animals experience during migration. Nowhere is this more evident than for migratory birds who “concentrate their hardship into a few days of extraordinary athleticism” (p. 102), rather than rough it out by overwintering in their summer haunts. Both godwits, who undertake the longest nonstop migration of any bird, and bar-headed geese, who ascend to extreme heights to cross the Himalayas, feature here. Similarly, microbial extremophiles, whether retrieved from Yellowstone’s hot springs or Earth’s deepest recesses, make an appearance.

“[…] anyone who has had to combat black mould in their house will be horrified, but likely not surprised, that researchers have found it growing on the walls of the destroyed reactor in Chernobyl […]”

Life’s diversity is such, however, that Riley can pull many other awe-inspiring examples out of his hat that were completely new to me. What to think of wood frogs in northernmost Alaska that freeze solid when hibernating? They deal with the extreme cold by filling their body with high levels of glucose that act as a cryoprotectant. In the process, their organs become disconnected from each other in both communication and function, to the point that, in the words of biologist Don Larson who studies them, “It’s not an organism anymore […] It’s parts of an organism that can come back and revive” (p. 122). And anyone who has had to combat black mould in their house will be horrified, but likely not surprised, that researchers have found it growing on the walls of the destroyed reactor in Chernobyl, capable of surviving levels of ionising radiation that would rapidly kill humans.

What I appreciated is that Riley walks that fine line between popularising science without sensationalising it. There are multiple examples where his respondents voice hypothetical ideas but, being trained to be cautious professionals, add the necessary caveats—Riley makes sure to include both. Arctic ground squirrels in Alaska enter a deep form of hibernation, reducing their metabolism a hundredfold. However, every three weeks or so, they warm up for about twelve hours while remaining inactive. Arctic biologist Brian Barnes thinks they emerge from hibernation to sleep (in the process highlighting that the two are not the same), while in the same breath admitting this is a hypothesis that has its critics. Ecologist Germán Orizaola studies the population of Przewalski’s horses thriving in the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Derived from a mere thirteen horses, they underwent a genetic bottleneck and Orizaola wonders if they actually benefit from the extra mutations induced by the chronic low-level radiation that remains, admitting that the idea is “hugely speculative” (p. 239). And the group of scientists proposing that the abovementioned fungi in Chernobyl are relying on a third way of making a living, radiosynthesis instead of photosynthesis or chemosynthesis, have their work cut out for them in convincing their peers, meeting with disbelief so far.

“[…] Riley walks that fine line between popularizing science without sensationalising it.”

Though Riley gives a nuanced picture of how science and scientists work, he ensures it remains accessible to non-scientists. He defines or briefly explains terms and concepts, whether it is the ecological niche, isotopes, signal-to-noise ratio, the trophosome (“a palace for symbiotic bacteria” (p. 212)), or something as mundane as the microscope slide. Some things he waves away: you do not need to remember the names of the different types of ionising radiation, just the principle that radioactivity results in “a range of projectiles that can penetrate the radionuclide’s surroundings” (p. 241). He similarly skirts around giving an explanation of how the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) works, boiling it down to its essentials: it allows you to amplify DNA from a very small initial quantity. Furthermore, Riley keeps the focus on the science, only occasionally adding a light dash of humour, or injecting asides about the private lives of his interviewees or his own mishaps while researching this book. It adds the necessary levity to keep the reader entertained without becoming a distraction. Riley has organised his text carefully, making sure no one section drags on for too long, and uses ornamental breaks to visually divide them. All these things combined make for an easy read.

One thing that might raise an eyebrow is the subtle theme of hope running through the book. I recently had the pleasure of attending a presentation of the book at my local bookstore, East Gate Bookshop, where Riley talked about this more explicitly. Having struggled with depression in the past (his first book was actually a history of how depression has been treated), he draws comfort from life’s resilience. More than once, he remarks that it is almost impossible to sterilise a planet once life has taken hold. Even as he cautions that “The examples in this book can’t balance the scales, nor should they be used as an argument to give up on those species that are threatened with extinction” (p. 10), he concludes in his epilogue that “Seen through the lens of deep time, extinction is a natural part of a living planet” (p. 271). If he appears somewhat blasé about the impending loss of biodiversity, the above bit of personal background helps to place this into context.

Overall, Super Natural succeeds at filling you with a renewed sense of wonder. With great persistence, Riley has sought out numerous interesting people and allowed them to explain in their own words what makes their study systems so exceptional. Even for seasoned readers, there is plenty here that will make you do a double-take.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

A really nice review, I’m quite convinced this must be worth it!

LikeLiked by 1 person