8-minute read

keywords: crime, reportage, wildlife conservation

This review is a case of coming late to the party. The Wolf (published in the USA as American Wolf) by Texas journalist Nate Blakeslee was published back in 2017, two years before wolf watcher Rick McIntyre’s series of books on famous wolves in Yellowstone National Park was published. I imagine most people will have read Blakeslee’s book first, but for me it was the other way around. Having just reviewed McIntyre’s The Alpha Female Wolf, which tells of the life and death of arguably the park’s most famous wolf, wolf 06, I was left with many questions regarding the hunting of wolves around Yellowstone. Blakeslee’s book turned out to be an excellent companion.

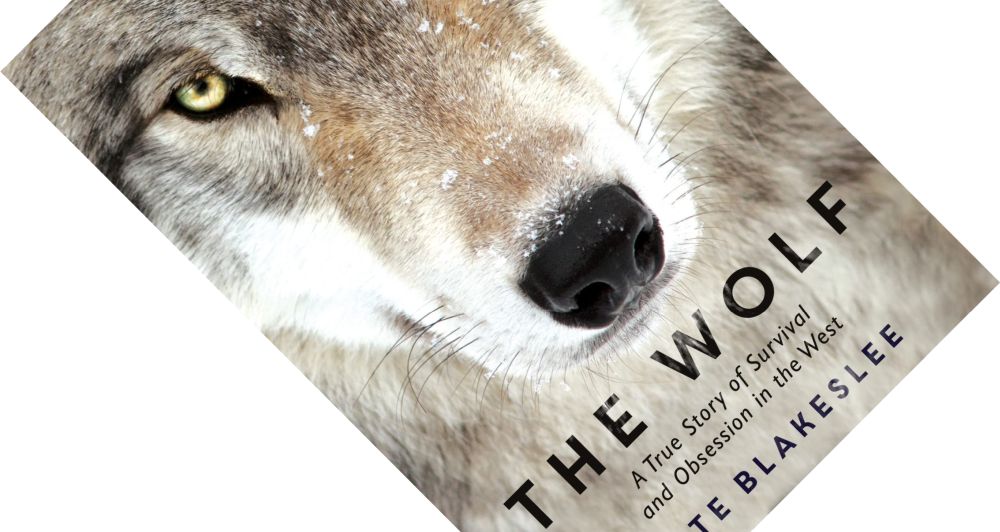

The Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West, written by Nate Blakeslee, published in Europe by Oneworld Publications in October 2018 (paperback, 320 pages)

Let me back up for a moment in case you are new to this topic. The reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 is widely considered a success story in wildlife conservation and they have since been intensively studied by biologists. Their daily lives have been scrutinized by a small cadre of dedicated wolf watchers, most notably Rick McIntyre who has written four books so far based on a lifetime spent in the park. From the start, however, hunters and ranchers in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho fiercely opposed the project, fearing the loss of quarry and livestock to wolves. As a compromise, the US Fish and Wildlife Service promised that the wolf would be taken off the endangered species list once the population had sufficiently recovered, allowing each state to draw up its own wildlife management strategy. Amidst many political and legal battles, this came to pass in 2009, meaning wolves could be legally hunted again. Against this backdrop, the Yellowstone wolves go about their daily lives, watched and admired by thousands of park visitors, with wolf 06 becoming a legend. When a hunter kills her in December 2012, it sets off a national furore. To Blakeslee falls the unenviable task to weave together all these threads into a coherent whole.

Having reviewed and enjoyed all four of McIntyre’s books, the storyline of the lives of the wolves in the park was familiar to me. Blakeslee has the advantage of having access to other dedicated wolf watchers and their notes, allowing him to present some of the highlights of this multigenerational wolf saga. The Druid Peak pack and wolves 21 and 42 feature, as well as the star of this book, their granddaughter 06. If you are completely new to this topic, the flurry of numerical designations and pack names might be somewhat confusing: the pedigree at the start of the book only shows 06’s lineage. Nevertheless, the narrative Blakeslee pieces together makes it clear why people get hooked on watching wolves.

“[…] the narrative Blakeslee pieces together makes it clear why people get hooked on watching wolves.”

Specifically of interest to me was the biographical sketch of McIntyre, as he barely talks about himself in his books. In my review of The Rise of Wolf 8, I mentioned his passion borders on the obsessive and Blakeslee confirms and fills out that picture for me. A sweet man possessed of a nearly child-like innocence, he is socially awkward and prefers his own company. The same compulsion that drove him to get the perfect shot in his previous career as a wildlife photographer, with some pictures published in National Geographic, now drives him into the park, at times risking his life to see wolves every single day. The thought of writing and promoting books, and thus leaving behind his daily routine in Yellowstone, makes him uncomfortable. And thus he keeps religiously recording everything he observes until it becomes an end unto itself. Fortunately for us, he eventually breaks that addiction, but not until two decades have passed.

The polar opposite of those who watch wolves are those who want them dead. Though, as Blakeslee shows, attitudes amongst hunters and ranchers are a bit more nuanced than that. Some, including wildlife biologists, argue pragmatically that predator populations need managing to protect livestock. Others, such as the man who killed wolf 10, will ride their horse down the local high street during Independence Day, proudly sporting a t-shirt that reads “Northern Rockies Wolf Reduction Project”. What many share is an aversion to outsiders, both out-of-state hunters and the wolf groupies flocking to the park. But I think Blakeslee captures the heart of the conflict when he writes that this is about federal overreach: “wolves were just the latest flashpoint […] the real struggle was over [management of] public land” (pp. 127–128).

And then there is the hunter who shot 06. A friend is willing to pass on Blakeslee’s contact details and the man, here pseudonymized as Steven Turnbull to protect his identity, reaches out to tell his story. An outdoorsman besotted with big-game hunting, he is unrepentant, boasting he would do it again. He is genuinely mystified by the enthusiasm of wolf watchers and maintains that he has done nothing wrong. I think Blakeslee gives a fair portrayal of Turnbull, allowing him to unload his story without judging him, although there are details he is not impressed with. To me, the whole concept of trophy hunting is just… alien, and coming to any sort of mutual understanding seems impossible. Blakeslee seems to feel the same when Turnbull shows him 06’s pelt and invites him to stand next to it to marvel at its size: “it felt profane, though I had no idea how to explain to my host why” (p. 261). Perhaps surprisingly, to me, Turnbull does not emerge as the book’s antihero.

“If there are villains here, they would have to be the governors and senators for who the wolves are just pawns in political power games. “

If there are villains here, they would have to be the governors and senators for who the wolves are just pawns in political power games. The wolf is delisted, declared protected, and then delisted again as various interest groups thwart each other through court cases and political shenanigans. This includes a very brazen overturning of a court ruling protecting the wolves via a last-minute provision snuck into a must-pass federal budget bill, a so-called rider. This was exactly the backstory that McIntyre, as a former National Park Service employee, carefully avoided commenting on in The Alpha Female Wolf. What also becomes painfully clear is that federal agencies, e.g. the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and various state agencies primarily serve the interests of hunters and ranchers. Wildlife protection is a happy coincidence if it happens to align with e.g. maintaining population levels of game.

Despite providing much sought-after context to the complicated situation around wolf reintroduction, the book did feel slightly uneven in places. Montana has always been a swing state in national elections, and in 2010 its Democratic senator is up against a Republican candidate who is making populist anti-wolf noises that are winning him votes. Admittedly, I’m not well-versed in US politics, but it seems a bit far-fetched when Blakeslee writes that “if Democrats were going to keep a toehold on power in Congress—if Obamacare was going to live past its infancy—wolves needed to start dying in Montana, in large numbers, and soon” (p. 158). Can national politics really be reduced to wolves? Similarly, when he covers the 2010 lawsuit that sought to return wolves to the endangered species list, the arguments from lawyers arguing in favour are given the most space, while the arguments from those against are described in a mere two pages. Furthermore, Blakeslee does not talk to any ranchers who lose livestock to predators, something Philippa Forrester did in her recent book on Yellowstone wolves. Finally, Blakeslee’s discussion of trophic cascades in the park as a result of wolf reintroduction tends towards a simplistic portrayal of wolves as some sort of canine fairy dust that you can sprinkle on broken ecosystems to fix them. Only in the source notes does he briefly mention that e.g. wolf biologist David Mech has warned against simplistic interpretations, something I also touched on in my review of Yellowstone Wolves.

This criticism notwithstanding, overall The Wolf succeeds in bringing together many disparate strands and weaving them into a captivating book. I found it a very useful companion to McIntyre’s writing but it also shines as a standalone book that tells of the fascinating lives of wolves in Yellowstone and the passions stirred by their reintroduction.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

3 comments