8-minute read

keywords: evolutionary biology, mammals, paleontology

Imagine being a successful dinosaur palaeontologist and landing a professorship before you are 40, authoring a leading dinosaur textbook and a New York Times bestseller on dinosaurs. Imagine achieving all that and then saying: “You know what really floats my boat? Mammals.” After the runaway success of his 2018 book The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs, palaeontologist Stephen Brusatte shifted his attention and now presents you with the follow-up, The Rise and Reign of the Mammals. Taking in the full sweep of mammal evolution from the late Carboniferous some 325 million years ago to today, this book is as epic in scope as it is majestic in execution.

The Rise and Reign of the Mammals: A New History, from the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us, written by Steve Brusatte, published in Europe by Picador in June 2022 (hardback, 500 pages)

Mammals shared our planet with the dinosaurs throughout their long reign, from the initial split of our amniote common ancestor into synapsids (us) and diapsids (them), to their extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. Over the course of some 100 million years, a parade of lineages evolved—archaic mammals all—piecemeal developing the traits we recognize as mammalian today: pelycosaurs with canine teeth, the first “whispers of a dental revolution” (p. 13); therapsids with the first hairs and a new form of metabolism, endothermy; the cynodonts, some of whom miniaturized while the dinosaurs became giants; the mammaliaformes who developed a new jaw joint; the docodonts and gliding haramiyidans who had fur; the multituberculates who had increasingly complex teeth; and the therians who gave rise to today’s placentals, marsupials, and monotremes. However, the above must not be mistaken for a linear march of progress. “[M]ammals were a still unrealized concept, which evolution had yet to assemble. […] they were not evolving [these traits] to become mammals. Natural selection doesn’t plan for the future” (p. 20). Simultaneously, it does not behove us to call these now-extinct groups evolutionary dead ends. “This is the privilege of hindsight. […] In their time and place, these mammals were anything but obsolete” (p. 88).

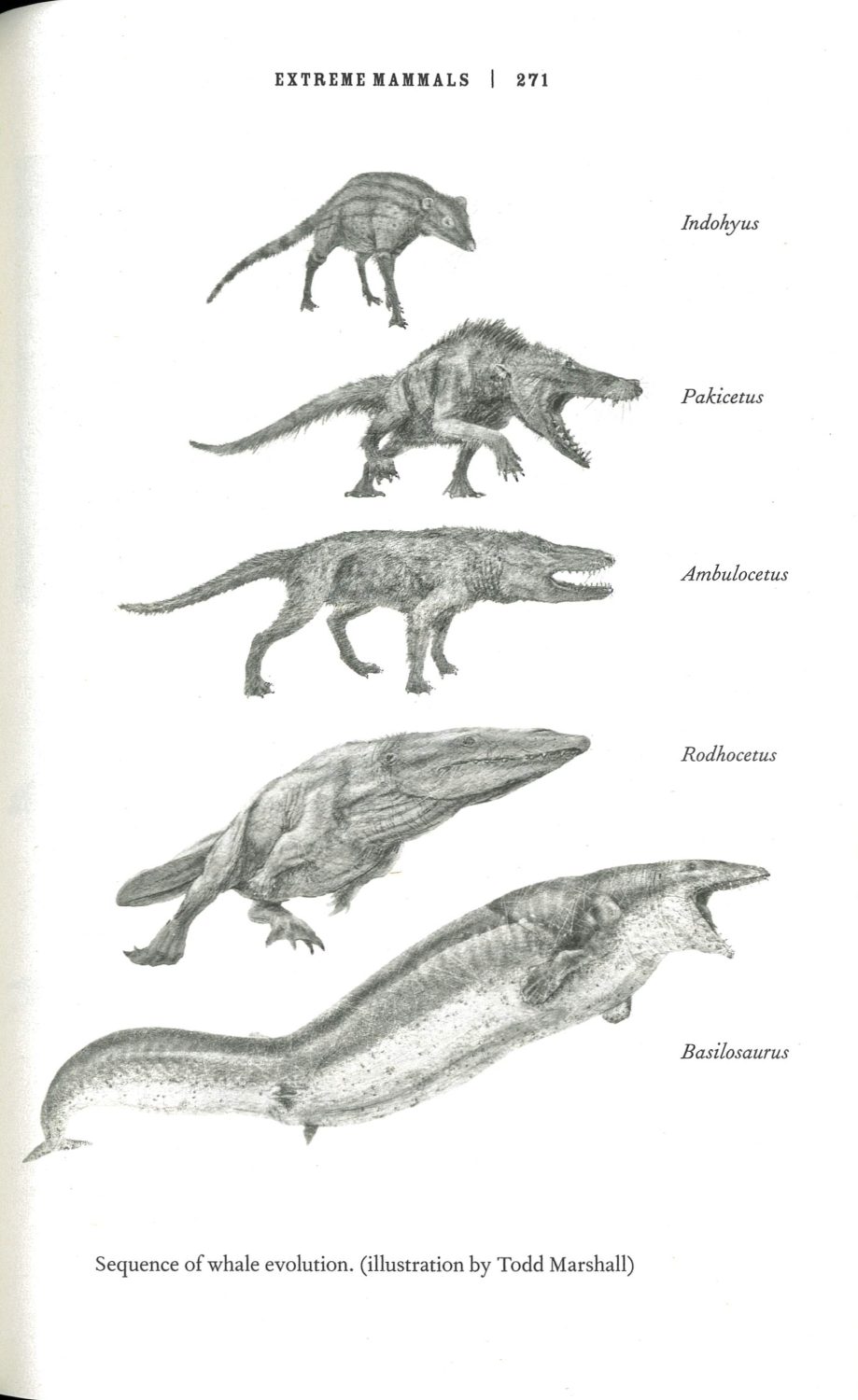

With the extinction of the dinosaurs, the rise of mammals turned into a reign. Isolated on various land masses after the supercontinent Pangaea had fragmented, they were poised for a slow-motion taxonomic starburst that would play out over the next 66 million years. In the northern hemisphere, multituberculates and metatherians were replaced by placental mammals who in the wake of the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum rapidly evolved into primates and the odd- and even-toed ungulates. The odd-toed ungulates spun off brontotheres and chalicotheres, some of the largest terrestrial mammals ever, while the even-toed ungulates spun off the cetaceans, some of the largest marine mammals ever.

With the extinction of the dinosaurs, the rise of mammals turned into a reign. Isolated on various land masses after the supercontinent Pangaea had fragmented, they were poised for a slow-motion taxonomic starburst that would play out over the next 66 million years. In the northern hemisphere, multituberculates and metatherians were replaced by placental mammals who in the wake of the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum rapidly evolved into primates and the odd- and even-toed ungulates. The odd-toed ungulates spun off brontotheres and chalicotheres, some of the largest terrestrial mammals ever, while the even-toed ungulates spun off the cetaceans, some of the largest marine mammals ever.

Brusatte’s strength is to bring to life the above flurry of names. What kind of creatures were they? And how can we deduce this from fossil evidence? Somewhere between chapters 6 and 7, I became awestruck by his narrative as the enormity of the mammalian evolutionary trajectory started to come into full view: bats took to the air, elephants evolved into a riot of tusked giants, South American native ungulates (origins: uncertain) flourished, monkeys and rodents rafted across the Atlantic to join them, metatherians migrated across Antarctica to Australia and spawned a spectacular marsupial radiation, grazers diversified as grasses went global, and somewhere at the end, hominins evolved and repeatedly spilt out of Africa, contributing significantly to recent megafauna extinction. What a wild ride!

“Over some 100 million years, a parade of lineages evolved, but this must not be mistaken for a linear march of progress, nor does it behove us to call these now-extinct groups evolutionary dead ends.”

The macroevolutionary story is fascinating in itself, yet Brusatte makes it even better with some interesting observations of his own. We usually think of the dinosaurs as dominating the mammals, but, he suggests, this went two ways: “While it is true that dinosaurs kept mammals from getting big, mammals did the opposite, which was equally impressive: they kept dinosaurs from becoming small” (p. 95). Furthermore, DNA studies suggest that many modern mammal lineages originated back in the Cretaceous. But where are the fossils? Could some of the poorly understood archaic placentals such as condylarchs, taeniodonts, and pantodonts be the missing fossils that we have not yet been able to link to modern groups because of the lack of signature anatomical features? Excitingly, Brusatte is part of a research consortium that is building a master family tree based on both anatomy and DNA.

As in his last book, Brusatte excels at explaining complex research methods and scientific concepts. One example is Tom Kemp’s concept of correlated progression. Several times during early mammal evolution, a whole suite of anatomical, behavioural, and functional traits were changing together, making it hard to unravel what was driving what. For instance when cynodonts shrunk in size and changed their growth, metabolism, diet, and feeding styles. Then there is the revision of the mammal family tree based on DNA sequencing. The classic tree, championed by zoologist George Gaylord Simpson in 1945, was based on anatomical features. By the early 2000s, DNA-based genealogies suggested that many supposed relationships were actually cases of convergent evolution, resulting in a new classification that reflected geographical patterns rather than anatomy. The new groupings came with some tongue-twisting names: Afrotheria, Xenarthra, Laurasiatheria, and Eurarchontoglires. A final example is tooth morphology, an important diagnostic trait in this story. Humans have a tribosphenic molar, a complexly-shaped affair. Interestingly, this is not a novel tooth shape but was already found in the 160-million-year-old Juramaia. At a time of competition with docodonts and haramiyidans, “the tribosphenic molar was a useful gadget for tiny insect-eaters, but not yet a game-changer” (p. 141). It became one when flowering plants diversified—and with them insect pollinators—some 100–80 million years ago. It is a brilliant example of what Neil Shubin highlighted in Some Assembly Required; that evolutionary innovations never come about with the great transitions they are associated with.

As in his last book, Brusatte excels at explaining complex research methods and scientific concepts. One example is Tom Kemp’s concept of correlated progression. Several times during early mammal evolution, a whole suite of anatomical, behavioural, and functional traits were changing together, making it hard to unravel what was driving what. For instance when cynodonts shrunk in size and changed their growth, metabolism, diet, and feeding styles. Then there is the revision of the mammal family tree based on DNA sequencing. The classic tree, championed by zoologist George Gaylord Simpson in 1945, was based on anatomical features. By the early 2000s, DNA-based genealogies suggested that many supposed relationships were actually cases of convergent evolution, resulting in a new classification that reflected geographical patterns rather than anatomy. The new groupings came with some tongue-twisting names: Afrotheria, Xenarthra, Laurasiatheria, and Eurarchontoglires. A final example is tooth morphology, an important diagnostic trait in this story. Humans have a tribosphenic molar, a complexly-shaped affair. Interestingly, this is not a novel tooth shape but was already found in the 160-million-year-old Juramaia. At a time of competition with docodonts and haramiyidans, “the tribosphenic molar was a useful gadget for tiny insect-eaters, but not yet a game-changer” (p. 141). It became one when flowering plants diversified—and with them insect pollinators—some 100–80 million years ago. It is a brilliant example of what Neil Shubin highlighted in Some Assembly Required; that evolutionary innovations never come about with the great transitions they are associated with.

“Somewhere between chapters 6 and 7, I became awestruck by Brusatte’s narrative as the enormity of the mammalian evolutionary trajectory started to come into full view.”

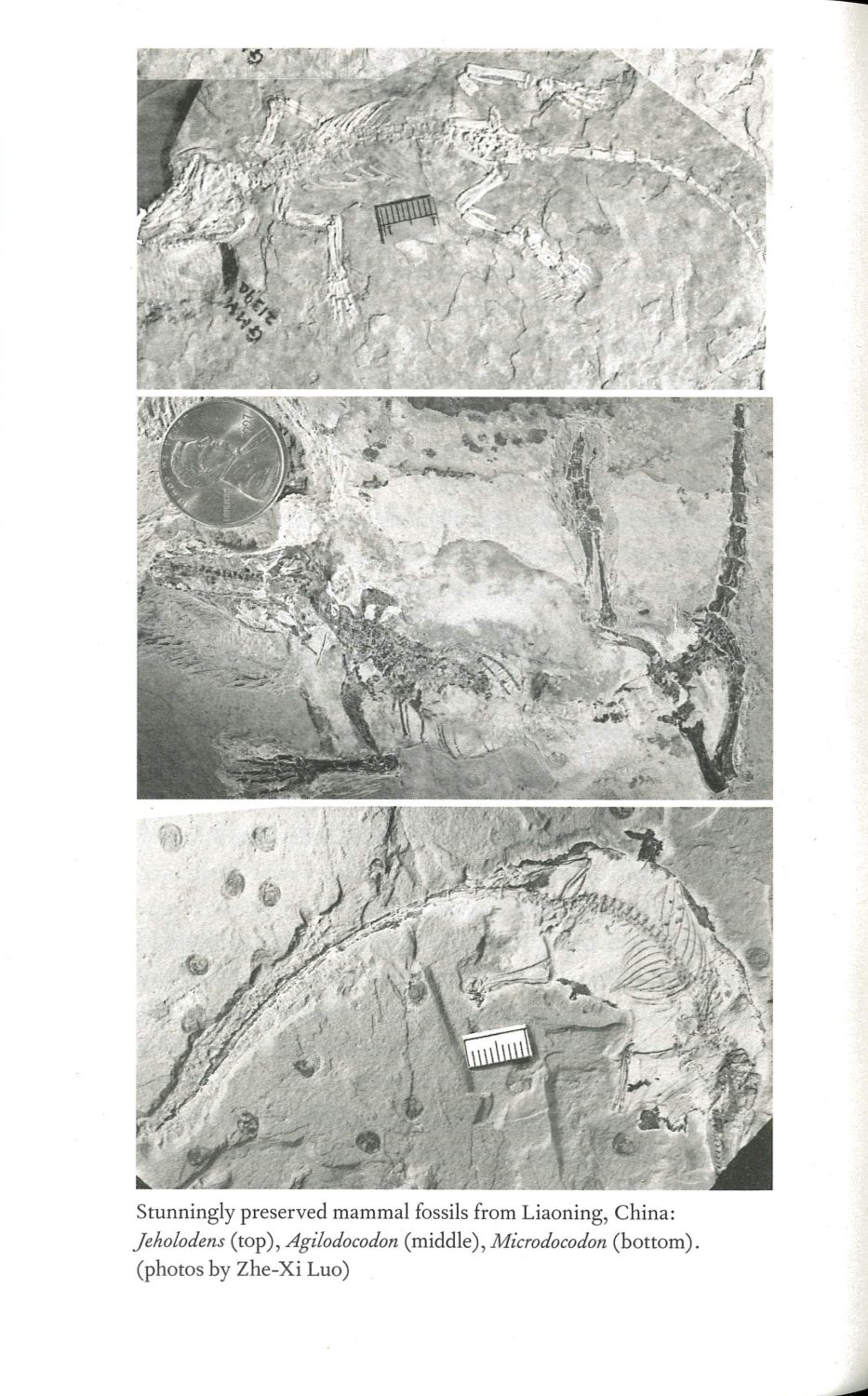

What helps with these explanations are some excellent illustrations. A selection of black-and-white photos shows amazing fossils. Todd Marshall has again been commissioned for both decorative chapter headings and some explanatory artwork. And Brusatte’s former student Sarah Shelley has contributed black-and-white diagrams that are exceedingly useful, illustrating for instance the remarkable changes in jaw bones and how some of these were repurposed to become our inner ear bones! I would be remiss if I did not mention the stunning jacket art. Both for the UK and US versions, the publishers have commissioned the same artists as for The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs, respectively Andrew Davidson and Todd Marshall, meaning the books look exquisite next to each other.

Woven throughout are stories of the people behind the research. Brusatte introduces the young scientists, such as Amusuya Chinsamy-Turan, who a is a pioneer in bone histology and gathered evidence in favour of endothermic therapsids; or his student Ornella Bertrand, who is an ace at CAT-scanning skulls and showed that most palaeocene mammals had unusually small brains. But he also includes many past scientists that are not widely known, such as Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska—who he visited at her home in Poland—and her expeditions to Mongolia; Robert Broom, who trained up some of today’s leading South African palaeontologists; or Walter Kühne, who discovered and described the tritylodontid Oligokyphus while held captive in a World War II internment camp.

Woven throughout are stories of the people behind the research. Brusatte introduces the young scientists, such as Amusuya Chinsamy-Turan, who a is a pioneer in bone histology and gathered evidence in favour of endothermic therapsids; or his student Ornella Bertrand, who is an ace at CAT-scanning skulls and showed that most palaeocene mammals had unusually small brains. But he also includes many past scientists that are not widely known, such as Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska—who he visited at her home in Poland—and her expeditions to Mongolia; Robert Broom, who trained up some of today’s leading South African palaeontologists; or Walter Kühne, who discovered and described the tritylodontid Oligokyphus while held captive in a World War II internment camp.

“By the early 2000s, DNA-based genealogies revealed that many supposed relationships were actually cases of convergent evolution.”

In what is surely a hallmark of his love and enthusiasm for the field, Brusatte’s bibliography has again been written as a narrative. It is like a chatty literature review in which he recommends books and papers, indicates where literature has become outdated, adds more technical details or clarifications, discusses where there is active debate and disagreement, and shortly touches on topics that he had to omit from the main narrative. Yes, this takes up more space than a regular reference section, and I am sure it is more time-consuming to write, but it is ever so useful. You could not wish for a better starting point if you wanted to read deeper into the technical literature.

Finally, you might be left wondering how this book compares to Elsa Panciroli’s Beasts Before Us which covered early mammal evolution up to the K–Pg extinction. There is overlap here in more than one way; Brusatte co-supervised her PhD project describing the docodont Borealestes from a Scottish fossil. I was therefore mildly surprised that he does not mention her book. There is some inevitable overlap as both books walk through the same groups, though Brusatte provides a fuller picture by covering mammal evolution up to today. Panciroli’s book stands out for its fantastic writing, though, so you cannot go wrong by reading them both.

The Rise and Reign of the Mammals is a more-than-worthy successor to The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs and has already secured a place in my personal top 5 for 2022. Brusatte convincingly shows that the evolutionary story of mammals is just as fascinating—if not more so—as that of the dinosaurs.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

The Rise and Reign of the Mammals

The Rise and Reign of the Mammals

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Thanks, ordered this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Hope you’ll enjoy it 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I ordered it too, even though I said that I’m not reading non fiction anymore.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh dear, I have created a monster…

LikeLike

I also recently finished Contingency and Convergence and wrote a post about it. Thanks for the reviews!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh nice, I’ll check that out!

LikeLike