9-minute read

keywords: evolutionary biology, history of science

Having just reviewed James T. Costa’s biography of Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, I was keen to read more about one of the most remarkable episodes in the history of science: how two scholars independently hit on the same idea and how history has largely forgotten one of them. Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species brings together many lines of evidence and analysis to argue that Wallace deserves recognition on the same footing as Charles Darwin as the co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection. This is a companion book to On the Organic Law of Change, presenting an analysis of this crucial notebook that Wallace kept during his travels around the Malay archipelago. Hence, you are getting a two-for-one as this review continues the previous one.

Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species, written by James T. Costa, published by Harvard University Press in June 2014 (hardback, 331 pages)

Now that you know what Wallace’s Species Notebook contains and why it is interesting, Costa here steps back to look at the bigger picture. One thing that Darwin and Wallace shared was that their arguments were consilient. Coined by 19th-century philosopher William Whewell as “consilience of inductions”, what this means is that they were drawing together many independent lines of evidence to build a convincing argument. It is a powerful way of reasoning and the stuff sound scientific theories are made of. Appropriately, I think Costa applies the same logic in this book, looking at this historical episode from many different sides.

Costa sets the scene by describing why Wallace travelled to the Amazon and the Malay archipelago, who his influences were, and what discoveries and publications his journeys produced. Two papers are of particular importance and are explored further here. Instead of their ornate Victorian titles, science historians refer to them as the Sarawak Law paper (1855) and Ternate essay (1858). In (very) brief, these papers respectively proposed that species change and how species change. Remember that this was when most naturalists, including prominently geologist Charles Lyell, were opposed to transmutation (as evolution was called), maintaining that species were divinely created, unchanging entities. In that sense, Wallace’s Species Notebook is a goldmine of the unpublished arguments he was considering and Costa’s analysis expands on the appendix in On the Organic Law of Change which only considered Wallace’s critique of Lyell.

The superficial narrative that Wallace and Darwin hit on the same idea at the same time is just that: superficial. To refine this story, Costa next compares the Species Notebook with Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (Origin hereafter), his pre-Origin notebooks, and his Natural Selection manuscript[1]. True, there are striking similarities in their conclusions and how they reached them, but there are also notable differences. Similarly, hindsight has compressed the timeline. Darwin had it figured out 21 years before Wallace but only shared his ideas with a few confidants, possibly made headshy by the strong condemnation of Robert Chamber’s book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Thus, their discovery of natural selection was contemporaneous, but not simultaneous; and it was similar, but not the same. Costa drives home these points because they are “an important first step toward realizing the independent nature of their respective insights” (p. 107).

“One thing that Darwin and Wallace shared was that their arguments were consilient. […] Appropriately, I think Costa applies the same logic in this book, looking at this historical episode from many different sides.”

Until 1857, Darwin and Wallace were unaware of each other’s thoughts on evolution but that would soon change. Darwin did not attach much importance to the 1855 Sarawak Law paper though at Lyell’s urging had started writing his Natural Selection manuscript. This would have become his big book until Wallace unintentionally forced his hand. First contact happened in April 1857 with a letter from Wallace, telling Darwin about his ideas on species change. Darwin sent an encouraging reply, noting they were thinking along the same lines and, “Oh, by the way”, he had been working on the species question for 20 years already and was making good progress on a book. In Radical by Nature, Costa brilliantly summarised what happened next: “If Darwin had a plan, it backfired” (p. 212 therein). By February 1858, Wallace had had his great insight, penned his Ternate essay, and enthusiastically replied to Darwin, attaching the essay with the request to forward it to Lyell if Darwin thought it had merit. When Darwin received this in June 1858 he was shocked, sending several anguished letters to Lyell. He had been scooped! He did not want to see years of hard work go to waste, but how could he possibly publish honourably at this point? In response, Lyell, together with Darwin’s other confidant botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, quickly organised the famous July 1st 1858 meeting at the Linnean Society.

To analyse this episode, Costa switches gears again and presents annotated facsimiles of all the key papers: the Sarawak Law paper and the papers read at the 1858 meeting; Darwin’s hastily written extracts of earlier material and Wallace’s Ternate essay. This is followed by a detailed analysis where Costa goes into the weeds on what their respective understanding of evolution was at this point in time. To give you a taste: the key difference Costa highlights is how they envisioned natural selection acts. Darwin thought speciation was primarily sympatric (species overlap in space) and driven primarily by competition leading to e.g. niche partitioning and diversification (his principle of divergence). Wallace, focused as he was on biogeography, thought speciation was allopatric (species are isolated in space) and driven primarily by environmental factors. Darwin was already discussing other modes of selection such as sexual selection (which Wallace long resisted) and colony-level selection in social insects. Reading the original papers is surprisingly fun. Beyond the somewhat flowery language and dated terminology that Costa clarifies, the logic shines through. Especially Wallace’s essays show how clued-in he was. For example, the fittest do not always survive: “there may be many individual exceptions; but on the average the rule will invariably be found to hold good” (p. 204). Environmental change can render well-adapted species less fit, and evolution happens “by minute steps, in various directions” (p. 212). To me, this shows a Wallace aware that evolution has no ultimate goal but is a never-ending game of organisms chasing shifting peaks in a fitness landscape. These are the kinds of subtleties we still need to remind people of today.

“Costa’s analysis next turns to the conspiracies and claims of misconduct. […] showing there is little more to them than the seductive scent of scandal.”

Costa’s analysis next turns to the conspiracies and claims of misconduct. Darwin has been accused of receiving Wallace’s Ternate essay earlier than mid-June, filching details from it, hastily rewriting sections of his manuscript and then using his influence to suppress Wallace’s claim to fame. Well now. Costa instead patiently dismantles these claims, showing there is little more to them than the seductive scent of scandal. He delivers, I think, an even-handed and fair discussion that earnestly explores suspicious-seeming details. What leaves the door open to “speculation and innuendo” (p. 234) is that several key letters are missing. And despite creative sleuthing by historians, Costa concedes that it is possible that Darwin received the Ternate essay earlier than he said. But what of it? He did not hide or destroy the evidence, forwarding it to Lyell as requested. More importantly, Costa’s preceding analysis has highlighted all the ideas Darwin proposed that are absent from Wallace’s essay and the Species Notebook. Thanks to plenty of documentary evidence (notebooks, manuscripts, and correspondence), historians have reconstructed how Darwin developed his ideas over the preceding years. Costa admits that Darwin might have been impressed, even influenced by the Ternate essay, but that “is not tantamount to intellectual theft” (p. 254). Furthermore, he thinks that Lyell and Hooker’s move is unethical by both contemporary and modern standards; they should have asked for permission before presenting these papers.

A final, interesting strand of the analysis considers some counterfactuals. What if Wallace had sent his essay straight to an editor for publication? Would Darwin still have published his book? Though we cannot know, Costa offers insightful speculation here. This all leads to the question of why we have forgotten Wallace but remember Darwin. There are several likely factors. The Darwin family was already famous thanks to grandfather Erasmus, and Darwin was admittedly poor at acknowledging others. Simultaneously, as Costa tells in Radical by Nature, Wallace’s generosity was near-pathological and he never stopped deferring to Darwin. He also championed questionable and controversial causes that raised eyebrows in scientific circles. Costa feels it is high time to right this wrong: “the scientific and broader intellectual community needs to do better by Wallace” (p. 262). However, as stated here and reiterated recently in Radical by Nature: “honoring Wallace certainly need not come at the expense of Darwin” (p. 414 therein).

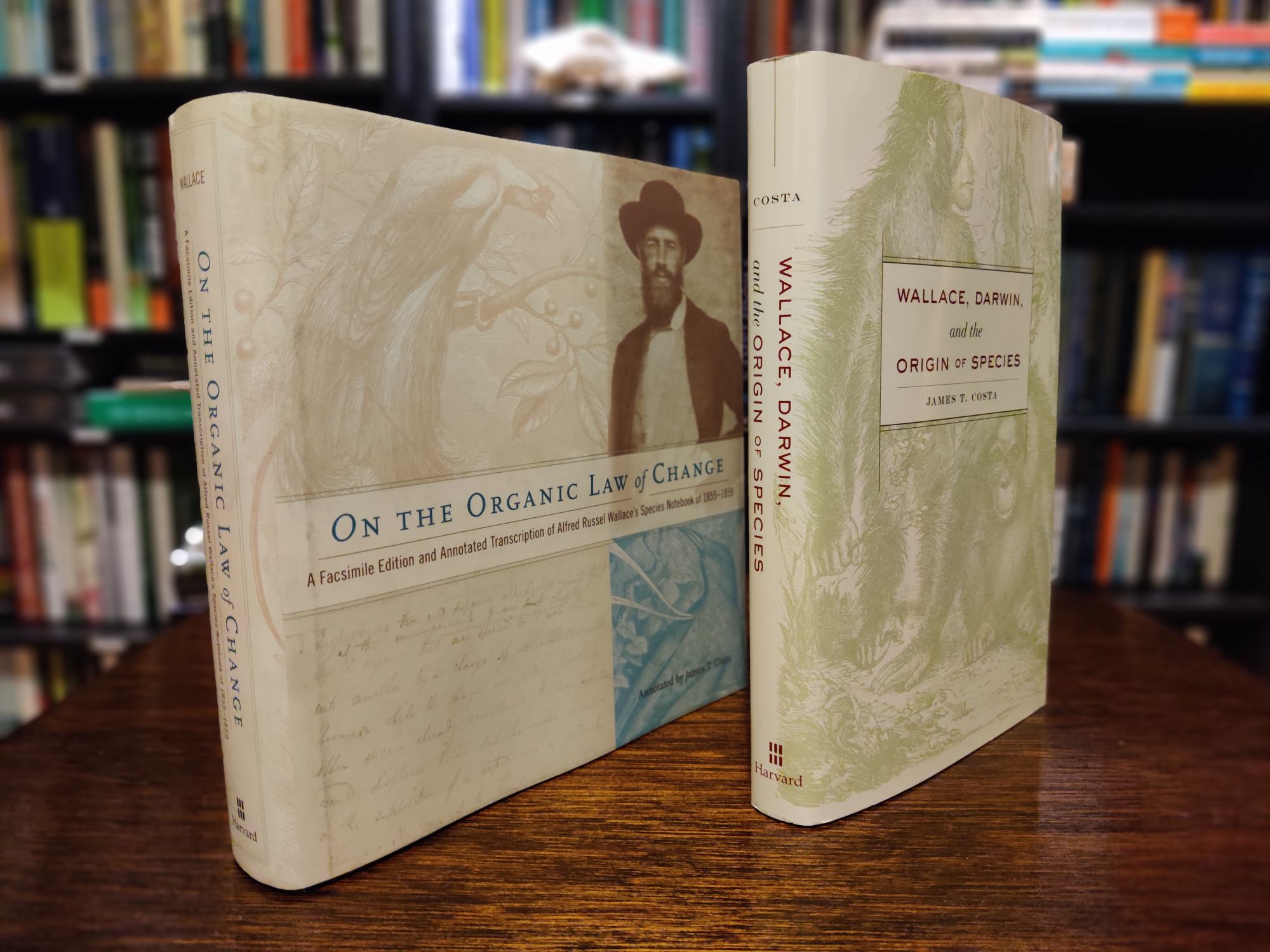

You may be left wondering if you can read On the Organic Law of Change by itself. You could, but then it is more of a historical curio. To get the most out of it you need this book. So, could you read Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species by itself? In principle, yes, it is mostly self-contained, but… just look at the two of them, do they not make a fine pair?

Also, note that the online version of the Species Notebook on the website of the Linnean Society has no transcription or annotations. So, to fully immerse yourself in this fascinating chapter of science history I would recommend you read them both. Costa has done a tremendous job on what clearly has been a labour of love. I commend the publisher for seeing the value in it and not forcing this into an abridged format.

1. ↑ Side-note here: Costa’s book acquainted me with a wealth of earlier work by science historians previously unknown to me, something that always increases my enjoyment of a book.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species

Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

in what order do you recommend to read the three books?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jac, relevant question, thanks for asking!

I would read them in the order reviewed here. Start with Costa’s biography, “Radical by Nature” to get a broad (and very enjoyable) overview of Wallace’s life and then read “On the Organic Law of Change” and “Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species” to zoom in on this specific episode in the history of science (i.e. how did these two men independently hit on the same idea, but why is only one of them remembered?)

As mentioned at the end of this review, there is little point reading “On the Organic Law of Change” by itself. To get the most out of it you need this book. The reverse is not true, so you could just read “Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species” and skip “On the Organic Law of Change” if you’re short on time or money. The former is mostly self-contained.

So, in principle you could limit yourself to just two books “Radical by Nature” followed by “Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species”. Though you might just as well immerse yourself fully while you’re here : )

LikeLike

Thnx-Yes..pretty hefty price tag on the ¨organic law of change¨ one ..but then again…they really do seem to make a nice pair : )

LikeLiked by 1 person