9-minute read

keywords: oceanography

“This isn’t merely a diverting tale about some salty water. This is the story that defines planet Earth” (p. 13). With that quote from the introduction, oceanographer Helen Czerski sets the tone for this book. In a break from many other books about the deep sea that talk about animals, Blue Machine focuses on the ocean itself, revealing a fascinating planetary engine. Equal parts physical oceanography, marine biology, and science history, topped off with human-interest stories, Czerski has written a captivating book that oozes lyricism in places.

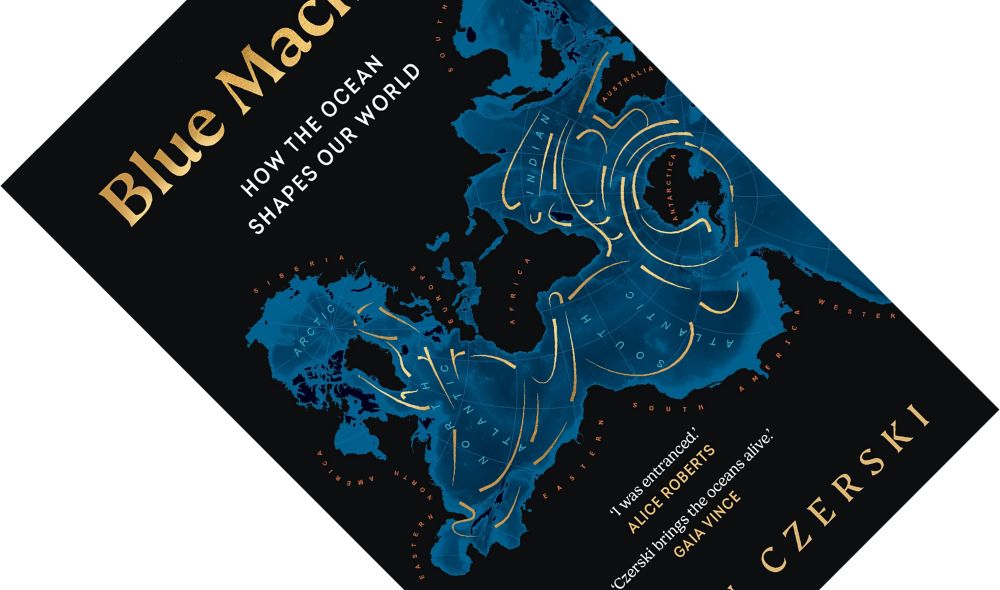

Blue Machine: How the Ocean Shapes Our World, written by Helen Czerski, published in Europe by Torva (a Transworld Publishers imprint) in June 2023 (hardback, 447 pages)

Czerski is an accidental oceanographer, stumbling into the discipline from a background in physics. She boasts a long list of science communication credentials as a TV presenter, podcast host, columnist, public speaker, and author, having previously written Storm in a Teacup and her Ladybird Expert primer on bubbles (her area of expertise). I find the deep sea endlessly fascinating and have been drawn ever further into oceanography through my reviews, yet something was always missing. This book has finally scratched the oceanographic itch I have long been trying to satisfy. How so?

Start with that introduction. If you zoom right out, what sets a planet’s temperature, and with it the potential for life, is the balance between energy input from the sun and energy loss to the universe in the form of heat (infrared radiation). From this grand, cosmic perspective, what the ocean with its circulating currents does is intercept some of that incoming energy and prevent it from immediately escaping again, instead “diverting it on to a much slower path through the mechanisms of the Earth: ocean, atmosphere, ice, life and rocks” (p. 5). From an energy point of view, “the Earth is just a cascade of diversions, unable to stop the flood but tapping into it as it trickles past; and the ocean is an engine for converting sunlight into movement and life and complexity, before the universe reclaims the loan” (p. 6). To me, this was such an awe-inspiring, attention-grabbing perspective on life on Earth, expressed so eloquently, that I wondered: is Czerski the new Ed Yong of oceanography? Tell me more, please!

“[I] have been drawn ever further into oceanography through my reviews, yet something was always missing. This book has finally scratched the oceanographic itch I have long been trying to satisfy.”

Blue Machine is Czerski’s third and biggest book yet, written in seven chunky chapters that mostly clock in at 60+ pages. She keeps the flow going, however, by alternating between scientific explanations and facts, fascinating experiments, and remarkable historical episodes. So let us have a look at each of these in turn.

What helps to understand the above idea of energy diversion is the fact that the ocean is a vast three-dimensional environment that is constantly in motion, creating and maintaining differences at different scales. Three basic parameters to consider are water temperature, which represents the heat stored by the ocean, salinity, which affects water density and thus drives its motion as parcels of water sink and rise, and Earth’s spin, deflecting this motion through something called the Coriolis effect. Heat and salinity furthermore create different layers of water that do not readily mix, meaning the ocean is stratified. This results in gigantic underwater conveyor belts that span the globe, and enormous underwater waterfalls near both poles where ice formation leaves behind saltier water that sinks, in the case of the Denmark Strait Overflow tumbling down 2.5 km into the depths of the North Atlantic. What makes these processes interesting is the shape of the container holding all this water: i.e. the position of the continents, the shape of their coastlines, and the topography of the underwater landscape with shallow continental shelves and deep ocean basins. Invisible to the naked eye, the local gravitational pull of the underlying rocks deforms the water surface over very large areas, creating domes and holes spanning tens of metres vertically, a shape known as the geoid. These are but some examples of the many fundamental features and principles of the ocean engine described in the nearly 200 pages and three chapters making up the book’s first part. Czerski admits that she cannot squeeze the full complexity of the ocean into one book, so topics covered in recent popular books such as tides, the origins of the ocean, or the interaction between oceans and past and future climate change are treated more briefly or not at all.

Admirably, Czerski is equally at home in the marine biology department and she features some wonderful critters here. There are the gargantuan shoals of lanternfish whose daily vertical migrations show up on sonar as a false ocean floor moving up and down, something that baffled oceanographers for decades. There is the extremely long-lived Greenland shark, a cold-water specialist with a life span of probably centuries. Or take Ramisyllis multicaudata, the utterly bizarre branching worm of many anuses—and I mean hundreds of anuses. And wait until you read about whale earwax(!), “one of those rare substances where evolutionary coincidence indulges scientific curiosity so generously that it feels like winning the lottery” (p. 247). Extruded by internal tissue but unable to escape a whale’s non-existent outer ears, it piles up inside and contains its life story. True, bizarre critters abound in all good popular science books about the deep sea. Helen Scales’s The Brilliant Abyss and Alex Rogers’s The Deep could give Czerski a run for her money, except that her physics background allows her to show how the physical and biological worlds intertwine. A beautiful example of this is the mesoscale eddies that are spun off by oceanic gyres: large islands of rotating water that are warmer or colder than their surroundings and become temporary havens for all the plankton and fish that find themselves inside. The formation of these wandering buffets is such a regular phenomenon that large ocean predators such as tuna can make a living by roaming the seas in search of them.

“bizarre critters abound in all good popular science books about the deep sea [yet] her physics background allows her to show how the physical and biological worlds intertwine.”

The second captivating element is the many ingenious experiments that she describes here, both historical and current. We almost developed a method to collect a long-term dataset on the global ocean’s temperature using sound. Several quirks of how the ocean works and is stratified mean that sound can travel around the globe, sound waves bouncing up and down in certain layers. A successful pilot experiment in 1991 deployed large oceanic speakers and a global network of receiving stations, but the idea never went beyond this proof of concept. More successful is the Continuous Plankton Recorder Survey which has been running for the last 90 years, with ships towing mechanical recorders that use elegant internal clockwork to capture plankton on long strips of mesh and have gathered valuable long-term records.

The third element to her book is how the physical world entwines with human history. Many organisms, humans included, will hitch a ride on currents if these take them somewhere useful, but the reverse is also true, “humans created ‘usefulness’ wherever the currents took them” (p. 186). One example is the narrow northern half of the Indian Ocean where gyres do not form but seasonal currents flow eastwards and westwards. The 14th-century Chinese Ming Dynasty used these to send expeditions of large ships laden with valuables up and down the coast of Asia and Arabia, trading goods for political influence and prestige. I was similarly captivated by the poorly known story of the 18th-century Scottish herring lassies: bands of female contractors who travelled south along the English coast each summer, pursuing the herring fleet, who pursued the herring, who pursued their copepod prey drifting south on the Gulf Stream’s currents. While the men worked the boats out at sea, the women were ready in ports and at beaches to gut, salt, and pack each day’s landing before the freshly-caught fish could spoil. Hard-working, skilled, and independent, they were decades ahead of most other women in Victorian England.

“Though a popular mantra in politics is that we need to follow the science, she opposes this “for the simple reason that science does not lead.” […] we have to decide what we [value] for ourselves and our communities.”

All of this is backed up by an attitude that, coming from a scientist, is refreshingly clued in to social issues. This becomes explicit in the final chapter where she addresses the environmental issues she has side-stepped so far. Though a popular mantra in politics is that we need to follow the science, she opposes this “for the simple reason that science does not lead. Where leadership comes from is a clear statement of values” (p. 381). Science can inform these, yes, but we have to decide what we care about for ourselves and our communities. Going down this path involves hard questions without simple answers, and nuance rather than binary “I am right, you are wrong” categories. It also means breaking with our perception of “the ocean as the end of a one-way pipe, [for] that is not how nature works” (p. 289). There is no “away” on this planet for our trash. And it means breaking with a culture “based on building and expanding and consuming and creating without having to think too much about the planetary life-support system” (p. 386). Her thinking here is influenced by her contact with Polynesian cultures that value cooperation, openness, and teamwork, in contrast to the Western mindset of ownership and power play.

If I need to sound a critical note it is the lack of illustrations. Though the UK version features nice endpapers and a stunning cover (a map of the world using the Spilhaus projection—there is a nice write-up on the ESRI website that shows John Nelson’s version with ocean currents that is used on the dustjacket), there are only two maps and two illustrations in the rest of the book. Especially some of the physical oceanography principles would have benefited from explanatory diagrams.

Blue Machine is an engrossing odyssey into oceanography. Czerski brings her substantial experience in science communication to bear on this topic and has written a transformative book. She brings to life the watery fabric of the ocean itself in ways I have not encountered before.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

3 comments