8-minute read

keywords: history of science, taxonomy

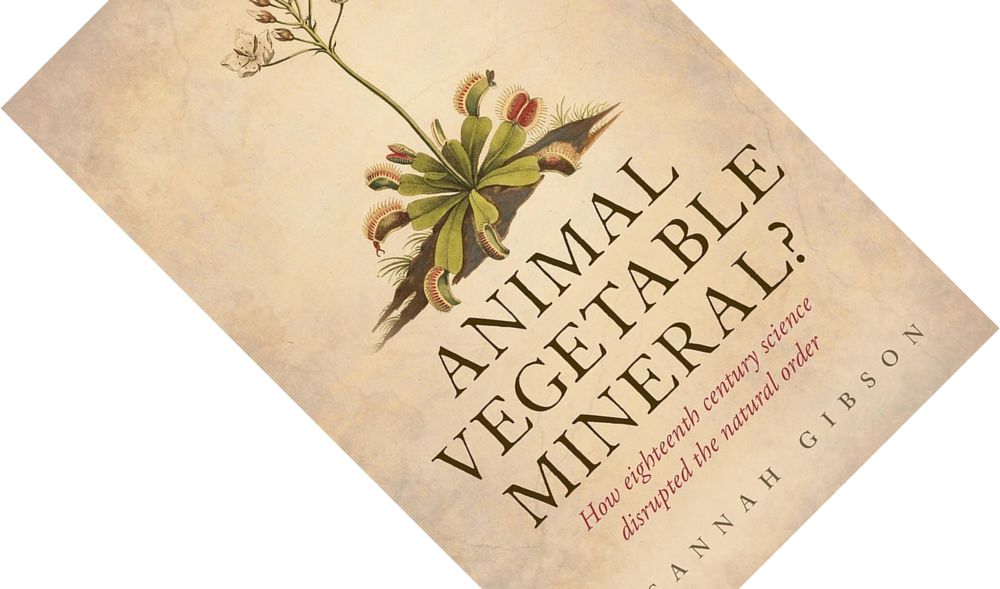

As a bonus to conclude my (now) four-part review series on the history of taxonomy, I am looking back to Susannah Gibson’s 2015 Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? After dealing with biographies of Linnaeus and Buffon, and then Ragan’s Kingdoms, Empires, & Domains, her book was just crying out to be read next. Given that those three were all published in 2023 and 2024, I will leave a comparison for the end of this review and first judge this book on its merits. As it turns out, this is an easy and intriguing read that I ignored for far too long.

Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? How Eighteenth-Century Science Disrupted the Natural Order, written by Susannah Gibson, published by Oxford University Press in July 2015 (hardback, 215 pages)

Gibson is an affiliated scholar at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge. Though she keeps a low profile online, a little research shows that since this 2015 debut, she has written two more books, The Spirit of Inquiry (2019) and Bluestockings (2024), showing a continued engagement with (science) history.

Even as I acknowledge Ragan’s point that dividing the natural world into animals, vegetables (i.e. plants), and minerals was neither rooted in prehistory nor universal, it cannot be denied that for centuries it was a widely accepted division. The 18th century was a time of radical change, though, with e.g. the French Revolution and the Scottish Enlightenment causing political and societal upheaval, while colonialism and empire-building brought home a raft of organisms previously unknown to Europeans. All this caused people to question traditional ideas and beliefs, including scholars who re-examined those creatures that had always straddled the border between different kingdoms. Importantly, while science was advancing rapidly, “this greater abundance of knowledge did not always lead to agreement” (p. 166), so Gibson connects her examples to larger debates of the era.

Zoophytes, those creatures that mix traits of animals and plants, are an appropriate place to start. She is on the ball in not attributing the term to Aristotle (as Ragan was at pains to emphasize in Kingdoms, Empires, & Domains), even as he got the whole zoophyte ball rolling with his interest in polyps, corals, sponges, and other marine invertebrates. They were still being discussed in the 18th century when naturalist Abraham Trembley garnered attention with his description and study of freshwater polyps (distant relatives of jellyfish in the animal phylum Cnidaria). Next to its biology combining elements of animals and plants, it has the remarkable ability to completely regenerate and multiply when cut into pieces. Trembley’s work fed into the larger ongoing debate between materialism (all is matter and energy, and matter and energy is all) and vitalism (living beings possess a special spark, a vital force). It spurred such questions as: “Is cutting a polyp into two a separate act of creation?”, “Is the soul then split into two?”, and “Where is God in all this?”

“while science was advancing rapidly [in the 18th century], “this greater abundance of knowledge did not always lead to agreement” (p. 166), so Gibson connects her examples to larger debates of the era.”

Linnaeus used sexual reproduction as a basis for plant taxonomy and drew analogies between animals and plants, even as his critics pointed to plants reproducing without seeds. This work in turn fed into larger debates about reproduction, which saw preformationism pitted against epigenesis. The former held that God had created everything in one go such that future offspring were stacked inside each other like so many Matryoshka dolls; the latter held that life resulted from the gradual organisation of disorganised matter via the laws of physics and chemistry—no God required. Note that Gibson illustrates this with animal rather than plant examples, including the historical dispute between Albrecht von Haller and Caspar Friedrich Wolff on chicken eggs and the unbelievable work of Lazzaro Spallanzani who kitted out male frogs with tiny waterproof trousers (!) to test the idea of egg preformation.

Gibson has a knack for uncovering some of history’s whackier tales. The chapter on minerals, which includes our struggle to understand fossils, might not feature a link to larger philosophical debates but does come with two intriguing character stories. The history of William Smith’s first stratigraphical map of Britain that relied on fossils has been told before, but the amazing story of Johann Beringer who fell victim to an elaborate hoax as he was trying to understand fossils was completely new to me. Here, as elsewhere, Gibson is a sensitive historian. Even as she defends some scholars from modern accusations of gullibility, pointing out that their methods and logic were sound but their knowledge a product of its time, she subtly scolds others for not crediting the unnamed slaves, fishermen, or gardeners who helped them make the observations for which they are remembered.

My only real criticism is that I am not fully convinced by one important line of her argumentation. She repeatedly contends that new findings in science had serious ramifications for society at large: “anything that could be used to show that nature didn’t always echo religious orthodoxy was dangerous […] abstract scientific questions could have all-too-concrete consequences” (p. 177). All this academic chatter of border-straddling animals and plants might cause people to question the natural order of things! I think it is an intuitively appealing idea, but what is the evidence for it? Yes, she shows how Linnaeus’s ideas on plant reproduction were readily satirized, even as they offered an opportunity to discuss sex in polite company. However, what were the “bigger religious and social implications” (p. 78) of the interest in Trembley’s polyp research? And how did the discovery of the Venus fly-trap that seemed to defy the God-given category of plants cause people to question social stratification? Maybe I am being too literal-minded, but did people ever revolt, pitchfork in one hand and scientific paper in the other? Could you not just as well argue that the revolutionary spirit in society bled into science, or, equally likely, that the two influenced each other? To my taste, much is asserted here without providing clear examples, though I will gladly admit my ignorance of this historical period. Perhaps the answer lies in her conclusion that in dismantling the familiar concepts of animals, vegetables, and minerals, naturalists gave society “a focus for asking a set of much bigger questions” (p. 188).

“Reading Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? a decade after its publication, how does it hold up? Actually, rather splendidly.”

To wrap up, I promised a comparison with the previous three books. Reading Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? a decade after its publication, how does it hold up? Actually, rather splendidly. For Linnaeus, Gibson relies on Lisbet Koerner’s biography and by and large agrees with Broberg’s book, except in a few details. For example, where Gibson writes that Linnaeus’s ideas were welcomed in England, Broberg argued this took time and the initial reception was lukewarm; and where she mentions the outrage caused by his writing on plant sexuality, Broberg contended this has been exaggerated. Gibson is briefest on Buffon but nails the core difference with Linnaeus that Roberts highlighted in Every Living Thing: Linnaeus preached an artificial system while Buffon countered that nature did not yield to such strict classification.

Most interesting is the comparison to Ragan’s book. Though Gibson’s first chapter is effectively an appreciation of Aristotle, she compresses the next two millennia. I think this is justified: as Ragan has so painstakingly documented, in essence not much happened beyond repeatedly redefining the concept of zoophytes. Even Cuvier remarked that Aristotle “left very little to do for the centuries after him” (p. 15). Gibson thus focuses on 18th-century developments while her epilogue is a speed-run through 19th and 20th-century biology. In a mere 215 pages, her book is of course no match for Ragan’s encyclopedic overview, but that was never the intention. That said, Ragan did not mention fossils or the wider social context. Can this book be a starting point if Ragan’s book seems too intimidating at first? If you finish it fascinated by zoophytes and want to immerse yourself deeply in the history of that concept, then, certainly, yes. But, more than a mere prelude, Gibson’s work readily stands on its own two feet even a decade later, covering subjects and stories not encountered in these three later books. Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? is a whip-smart book that I ignored for far too long.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Have you encountered “The Light Eaters” yet? I’m reading it presently and there’s some brief discussion of how taxonomy was used to dismiss any conception of plants having awarenesss/responsiveness.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, no, I haven’t yet, though it is high on my to-do list.

That’s interesting to read and agrees with what Ragan said about the long influence of Aristotle’s ideas (plants were supposedly different from animals by having spirit and life but not perception)

LikeLike

That’s discussed in Light-Eaters, as well; Aristotle’s view is compared against that of Theophrastus’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice, definitely need to get to this one!

LikeLike