7-minute read

keywords: cognitive science, evolutionary biology, psychology

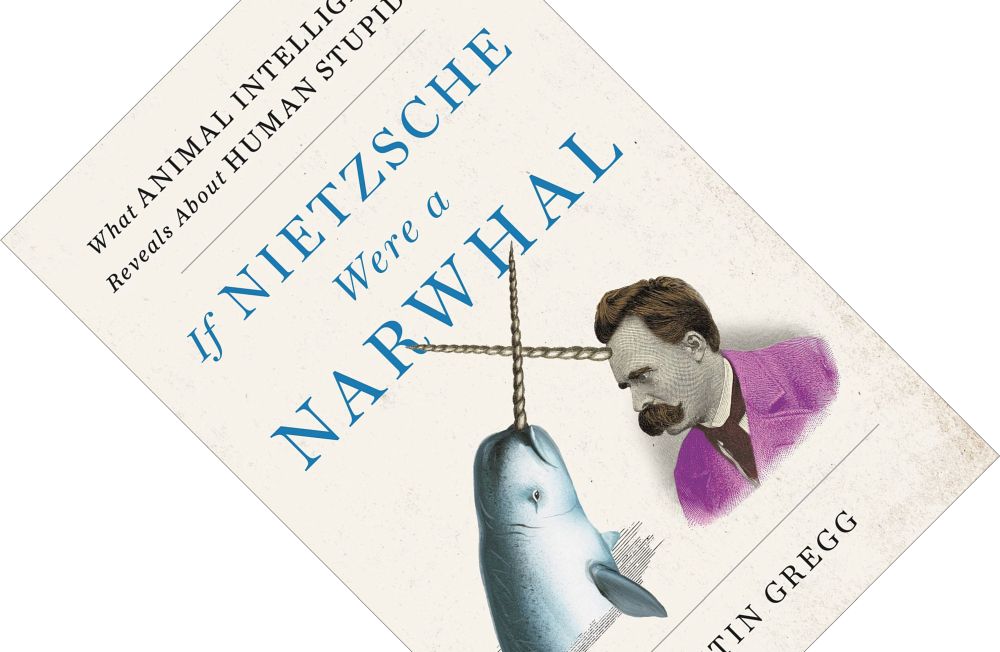

From the absurdist Terry-Gilliam-style cover to the provocative subtitle to my enjoyment of his previous book Are Dolphins Really Smart?—I had high hopes for this book. Justin Gregg is an Adjunct Professor lecturing on animal behaviour and cognition, and a Senior Research Associate with the Dolphin Communication Project, betraying his particular interest in marine mammals and animal language. Holding forth the provocative idea that our intelligence is a burden rather than a boon and that animals do it better, If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal combines well-aimed philosophical potshots at human exceptionalism with a gentle introduction to animal cognition. A blissfully easy read, this book had me in stitches more than once.

If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal: What Animal Intelligence Reveals about Human Stupidity, written by Justin Gregg, published by Hodder & Stoughton in January 2023 (hardback, 309 pages)

There is no denying that humans are smart creatures, and a vast gap seems to yawn between us and even our closest primate relatives. Why? The reason that we do not see more of it, Gregg argues, is that human-level intelligence is surplus to requirements: other animals can get by just fine with less. The conclusion to his introduction sets the tone for the book and reeled me in: “What if we acknowledge that sometimes our so-called human achievements are actually rather shitty solutions, evolutionarily speaking? Doing that turns the whole world upside down. […] The animal kingdom suddenly explodes with beautiful, simple minds that have found elegant solutions to the problem of survival” (p. 16). From that perspective, we are not the pinnacle of evolution but an aberration, an unnecessarily brainy ape. To buttress this provocative idea, Gregg compares several cognitive traits in humans and other animals: the ability to ask “why” (causal inference); language and the deceptions it allows; awareness of mortality; norms and morals; consciousness; and an exceptionally dangerous form of human cognitive dissonance he dubs prognostic myopia. I will look at some of these in more detail below.

Gregg calls humans the Why Specialists. Whereas other animals learn by association, humans can additionally learn through inference. For him, this demarcates a boundary: “our understanding of cause and effect is the source from which everything else springs” (p. 32), the skill at the root of all our achievements. But is it useful? After all, “animals can make fantastically useful decisions without the need for asking why things happen” (p. 49). Causal reasoning has sent us down some dark and dangerous paths in the past, from the humoral theory in medicine to scientific racism. And though the scientific method can ferret out real phenomena, this takes time, “which allows our why specialist yearning to churn out crappy, humorism-style answers in the meantime” (p. 48).

“sometimes our so-called human achievements are actually rather shitty solutions, evolutionarily speaking […] From that perspective, we are not the pinnacle of evolution but an aberration.”

Really interesting, I thought, was Gregg’s next argument. Our advanced cognitive traits have also resulted in some unintended byproducts. He applies this in particular to mortality and morality. Though the idea that animals can grieve is popular, even a proponent like Barbara J. King cautions that “we alone fully anticipate the inevitability of death” (p. 96). Quoting philosopher Susana Monsó, Gregg adds that “grief does not necessarily signal a [concept of death] – what it signals is a strong emotional attachment to the dead individual” (p. 95). Gregg is convinced that death means something to other animals, a topic studied by the recent field of comparative thanatology, though it does not seem that they understand their own mortality. Humans do, but does this do us any good? From an evolutionary standpoint, this is largely irrelevant. Understanding death “relies on cognitive skills that are [otherwise] hugely beneficial to the human ability to understand how the world works (e.g., mental time travel, episodic foresight, explicit knowledge of time)” (p. 114). In short, it is a bug, not a feature. He applies the same reasoning to human morality. Primatologist Frans de Waal has argued that human morality is “a natural outcropping (shaped by evolution) of behavior and cognition that is common to all social animals” (p. 125). They live by codes of conduct known as norms, and Gregg argues that the human moral sense has been moulded “from the clay of animal normativity” (p. 127). However, our morality does not prevent us from justifying to ourselves atrocities such as homophobia, racism, and even genocide. So what good are morals? He considers them another byproduct of e.g. language, theory of mind, and our why specialism. Unfortunately, “you can’t unlink these things. You cannot have that laundry list of positive cognitive skills without the negative consequences” (p. 154).

The final example, explored in the last two chapters, is what Gregg calls prognostic myopia: our shortsighted farsightedness. In a nutshell, this brand of cognitive dissonance is “the human capacity to think about and alter the future coupled with an inability to actually care all that much about what happens in the future” (p. 195). Our brains evolved to deal with immediate problems, and we employ technology to solve them, but we are simply not wired to care about the long-term, unforeseen consequences these solutions generate. Gregg considers it the most dangerous flaw in our thinking, and climate change the prime example of existential threats it can lead to.

“Understanding death “relies on cognitive skills that are [otherwise] hugely beneficial to the human ability to understand how the world works […]” In short, it is a bug, not a feature.”

Now, provocative and fascinating as these and other ideas are, I do feel that Gregg generalizes and oversimplifies in places. Returning to the above examples. Why did it take so long for us to evolve into why specialists? Because sometimes it leads to ludicrous solutions, Gregg answers. That is an amusing observation but does not answer the question. Regarding death awareness, he rather dramatically portrays it as a singular moment in time where a human child developed it, surrounded by adults who could not understand her experience, which seems rather far-fetched. Ants, meanwhile, are easily misled: spray a live ant with the pheromones of a dead ant (so-called necromones), and its nestmates will summarily carry the protesting ant out of the nest. But does that mean, as Gregg concludes, that ants have little understanding of death? Or rather, as Ed Yong has written elsewhere, that we fail to understand animals on their terms? In a world dominated by smell, they seem to understand death perfectly well. Even though Gregg references Nagel’s famous paper later on, here he seems to forget to ask what it is like to be an ant. Similarly, I consider prognostic myopia a very powerful concept, but to pin our inaction in the face of climate change on this one cognitive flaw alone oversimplifies things. Judging by some other books on this topic, things are a little bit more complicated than that.

In my review of his previous book, I warned readers to buckle up for some serious terminology. This book is an improvement and I was impressed with his accessible explanations of complex concepts such as theory of mind or metacognition. I particularly liked his ingenious metaphor of improv theatre to explain consciousness. Imagine your mind as a theatre, the spotlight as your subjective experience (i.e. consciousness), and the various players on stage as things you can be conscious of. Crucially, the difference between humans and other animals is that we have many more “cognitive processes that [can] step into the spotlight of consciousness and generate qualia for us. We’re not more conscious, we’re just conscious of more things” (p. 177).

In conclusion, If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal is irreverent and frequently funny. For those who read those books or my reviews of them; in tone it is closer to Barash’s Through a Glass Brightly than to Money’s misanthropic The Selfish Ape. Even if I am critical of some finer points, Gregg had little trouble convincing me that humans should not be too impressed with themselves and that animals show that such cognitive chops are surplus to requirement. Here, too, it seems that being good enough suffices.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

5 comments