7-minute read

keywords: art, biography, paleontology

Jay Matternes is one of the more underrecognized palaeoarists. Born in 1933, he has laboured away as a freelance artist in relative obscurity for over six decades. In 2020, I reviewed Visions of Lost Worlds which celebrated the six large prehistoric mammal murals he painted for the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. I concluded that review by asking about the rest of his career and suggested this was an area ripe for a biographer. Little did I know that such a book was already in the making and it flew under my radar[1] until very recently. As if the prospect of more artwork by Matternes was not enough, when I saw that it was authored by Richard Milner, who wrote the de-facto career retrospective of renowned palaeoartist Charles R. Knight, I was positively salivating. To say that I am pleased with the result would be putting it mildly.

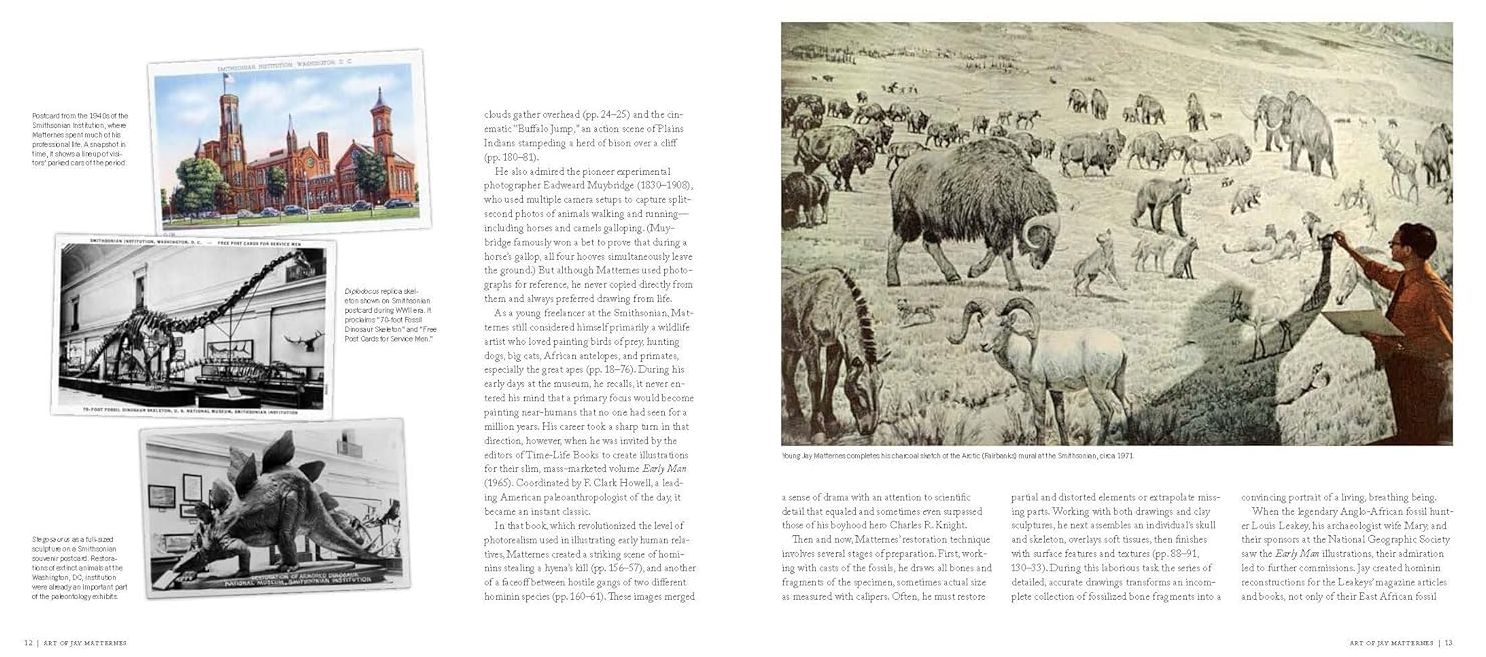

Jay Matternes: Paleoartist and Wildlife Painter, written by Richard Milner, published by Abbeville Press in August 2024 (hardback, 180 pages)

Before delving in, let us take a moment to appreciate the presentation of the book itself. The dust jacket is graced with a close-up of the striking 1998 painting The Fight on the Pan, depicting a pride of lions tackling a Cape buffalo. The choice of contemporary wildlife seems appropriate to show that Matternes has more strings to his bow than just his palaeoart. Remove the dustjacket, however, and a detail from the Alaskan mammoth steppe mural, showing life in the late Pleistocene, wraps around the casing. Nice. The endpapers each show a close-up of the wonderful double painting Day and Night in the Sonoran Desert, published in a 1972 book by National Geographic. It shows the same desert landscape at two different times of day and has some lovely visual details for those paying close attention. At 28 × 25.5 cm (W × H), the book is of comparable dimensions to Visions of Lost Worlds (27 × 27 cm). But, enough about the presentation, what of the contents?

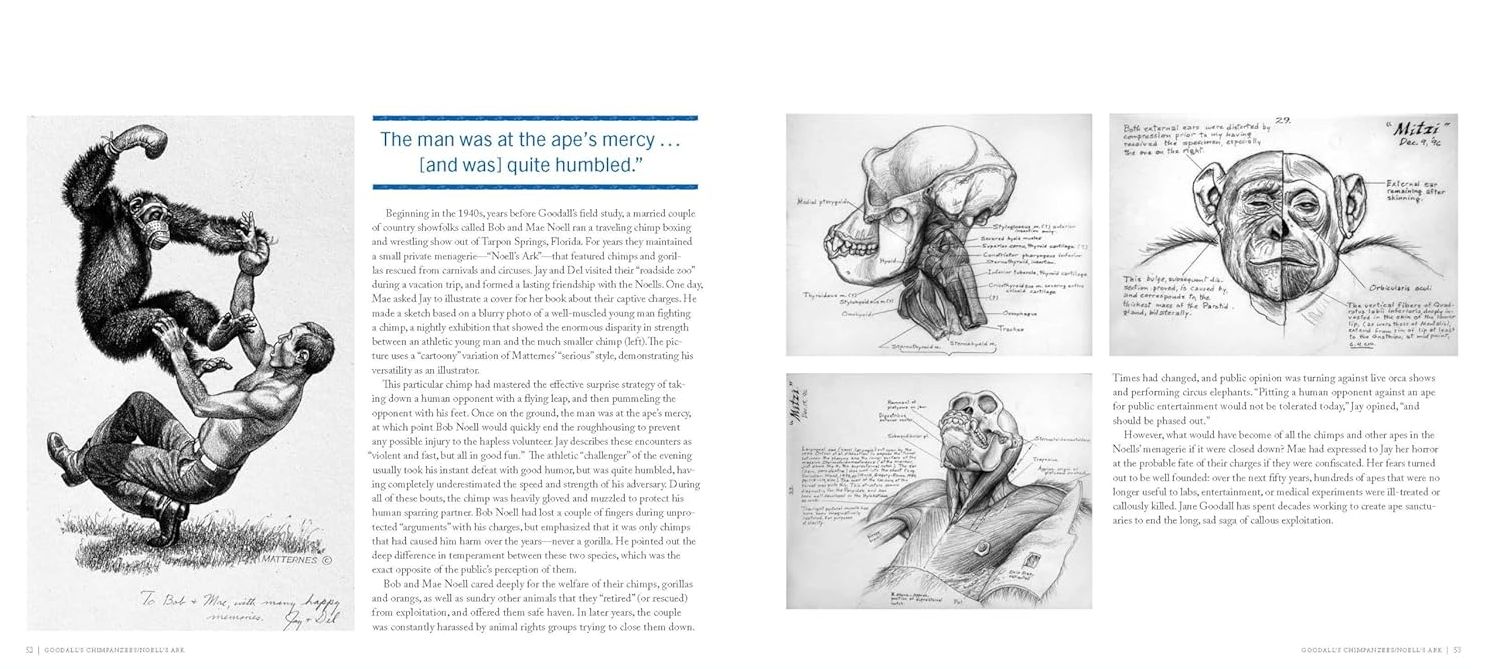

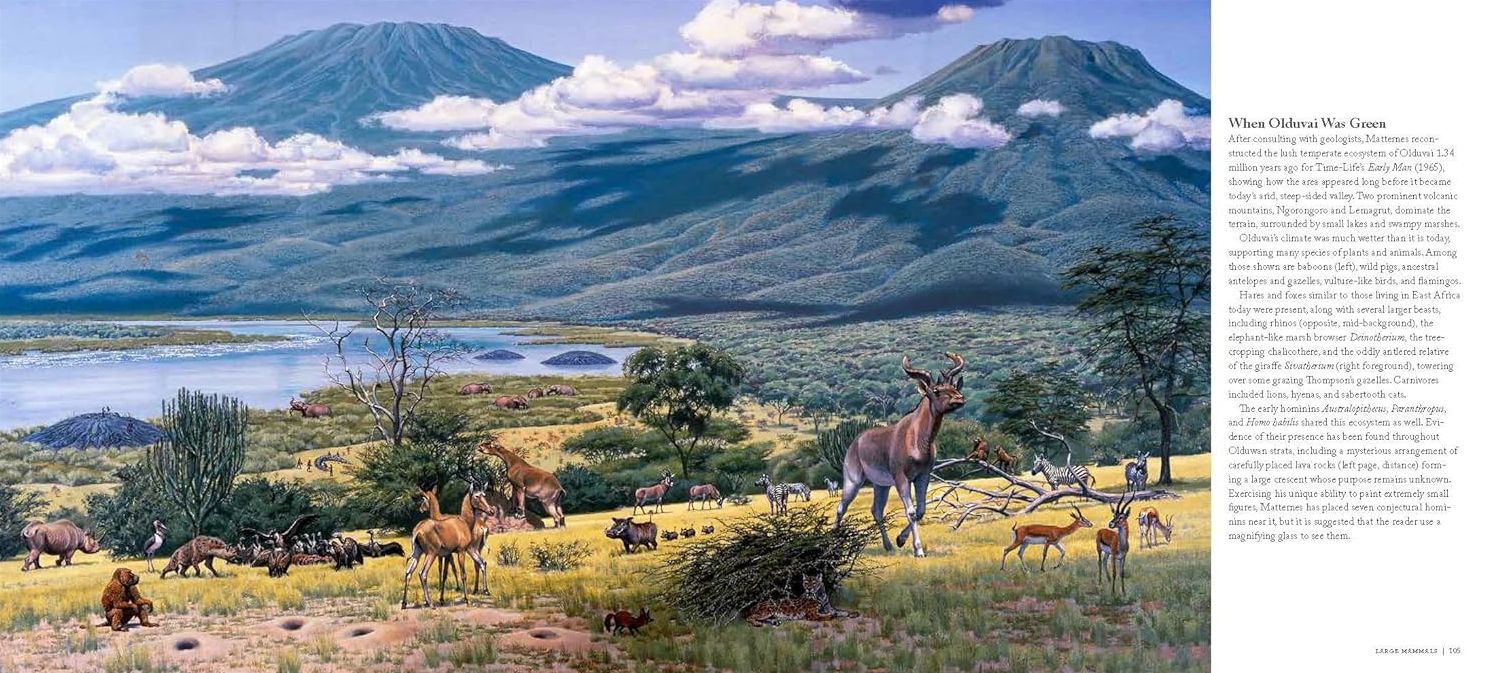

The visual content of the book is, in a word, mesmerising. There are landscapes depicted here that make me want to inhabit these illustrations (for example When Olduvai Was Green on pp. 104–105). Milner does not follow a strict chronological sequence but has organised the illustrations into five loose groups: contemporary wildlife, primate studies, prehistoric mammals (and a few dinosaurs), palaeoanthropology, and historic illustrations. The material has been drawn from a range of sources: Matternes’s personal archives, books published by Time–Life and National Geographic that older readers might recognize, and some rare pieces now housed in museums. A good example of that last category is Hippo Feast at Ileret, which was painted specifically for a 1976 documentary for a camera to slowly pan over during a narrative sequence. It was subsequently donated by the filmmakers to the Kenya National Museum, so you are unlikely to have seen it before. Several such exhibit pieces have been especially photographed for this book. Most illustrations are finished works, but there are also some gorgeous sketches (especially in the section on primates) that show the amount of research and reconstruction Matternes puts into each piece. Pleasingly, the reproduction is such that his handwritten notes are legible. Given that the Smithsonian murals were covered at length elsewhere, there is an appropriate lack of focus on these here, with only three of the six murals reproduced. If you want to know more about those, do yourself a favour and get Visions of Lost Worlds. You can thank me later.

“The visual content of the book is, in a word, mesmerising. There are landscapes depicted here that make me want to inhabit these illustrations.”

Do not let the glut of visual content fool you into thinking this is “just” a coffee-table book, though. Sure, there is the expected brief introductory chapter that gives a biographical sketch. However, Milner has spent eight years researching this book[2] in close collaboration with Matternes. What elevates it to a proper career retrospective is the narrative and commentary throughout the remainder of the book, which serves three goals.

First, the text contains descriptions of the images: what are you looking at and why has it been depicted this way? Since these illustrations have been produced over many decades, Milner provides additional context by explaining what the scientific understanding was at the time, and how it has changed since. As mentioned in the introduction, “Because of his obsession with scientific accuracy, Matternes’ drawings and paintings provide a unique history of the progress of paleoanthropological knowledge” (pp. 14–15).

Second, the text contains additional biographical information and amusing anecdotes. A particular highlight was the find of a trove of original sketchbooks and letters from a 20-year-long correspondence with primatologist Dian Fossey that had been gathering dust in a closet at Matternes’s home. Milner has included a selection of sketches and letters here that provide some particularly private details that, as far as I know, have not been published before. Matternes is not mentioned in Camilla de la Bédoyère’s book Letters from the Mist, for example.

“Milner has spent eight years researching this book […] and I am so pleased that {he} both took his time to write this book, and was able to see it through to completion together with Matternes.”

Third, there are insights into Matternes’s process. Several drawings show his three-step approach, first creating a skeletal reconstruction, measuring individual (fossilised) bones with callipers; then reconstructing the musculature, drawing on his knowledge gained from dissections; and finally reconstructing the life appearance of his animal subjects. Similarly, Matternes has visited many of the landscapes he depicts in his drawings to take notes and make sketches. In The Palaeoartist’s Handbook, Mark Witton wrote a chapter on the importance of researching your subject, and Matternes embodies these principles. A particular highlight here is his involvement with palaeoanthropologist Tim White in reconstructing the extinct hominin Ardipithecus ramidus. In absolute secrecy, he worked on this project on and off for eleven years, clocking hundreds of hours measuring and sketching bones, going through multiple cycles of feedback and revision with the scientists involved, and finally producing several life reconstructions and anatomical drawings that formed an important part of the 2009 media spectacle orchestrated by White. The real kicker in this story? This was a labour of love for Matternes, “there was nothing in the scientific budget to pay an artist; and nobody sought to reimburse him for his unique and expert contribution” (p. 137). He has subsequently barely been credited. Even Kermit Pattison in his book Fossil Men only pays lip service to his role, condensing it into a single sentence. “Ardi came to life in beautiful, life-like drawings by anatomical artist Jay Matternes, an old master of natural history artists who also had illustrated the Laetoli footprint walkers and even the Time–Life books on evolution that had captured the imagination of the teenage Tim White” (p. 355 therein). Milner here thus uses the opportunity to put the record straight.

In conclusion, I have nothing but praise for this book. The production values are top-notch and I am so pleased that Milner both took his time to write this book, and was able to see it through to completion together with Matternes. Now we have not one, but two books celebrating his artwork. That in itself is well-deserved. However, this career retrospective is also a very necessary book given the narrow focus of Visions of Lost Worlds. If you love palaeoart, or wildlife art more generally, this book is a must-buy and, for me, is a contender for this year’s top 5.

1. ↑ Funny anecdote here: After I reviewed Visions of Lost Worlds, Matternes gave me a phone call and during our chat mentioned that he was working on a book, but could obviously not reveal much more. I subsequently forgot about it (!) until a few weeks ago when foreword author Mauricio Antón tweeted about the imminent book launch.

2. ↑ For those wondering about palaeoanthropologist Ian Tattersall being given second billing on the cover. As “About the Authors” on p. 196 clarifies, Tattersall instigated this retrospective, having worked with Matternes since the early 1990s, and then invited Milner to complete the project. My impression is that the lion’s share of the research and writing was done by Milner.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

2 comments