Being turned into a zombie is not something most of us worry about. Sure, some of us consider humans metaphorical zombies, controlled by mass media / the government / smartphone addiction / my pet hamster / ________ (fill in your own favourite 21st-century angst here). All I can say after reading Matt Simon’s book is that I am glad that I am not an insect. In turns gruesome and hilarious, Plight of the Living Dead is a carnival of the many grotesque ways that parasites can control their hosts. Something we do not have to worry about… or do we?

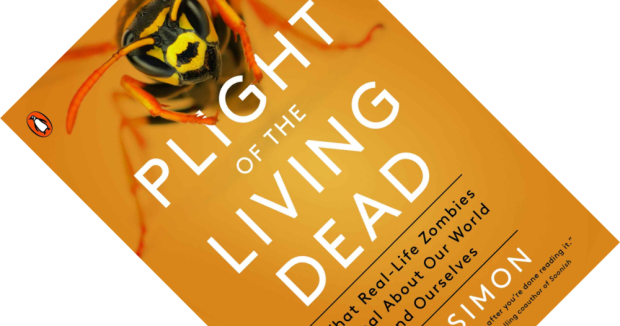

“Plight of the Living Dead: What Real-Life Zombies Reveal About Our World – and Ourselves“, written by Matt Simon, published by Penguin Books in October 2018 (paperback, 237 pages)

When I picked up this book I could not help but think: “Hang on, didn’t he just write a book about this?” The title of Simon’s previous book, The Wasp That Brainwashed the Caterpillar: Evolution’s Most Unbelievable Solutions to Life’s Biggest Problems, indeed seems to suggest so. And although zombies featured in that book, it is more a collection of stories about evolution’s many marvels. The zombie story has plenty of mileage, however, so he dug deeper for this book.

In eleven witty and short chapters, Simon gives a whirlwind tour of the many bizarre parasites that affect especially insects. If the idea of having lice or worms already freaks you out, how about the jewel wasp that stings a cockroach in its brain to pacify it, after which it lays an egg on its belly? The wasp larva that crawls out will slowly consume the cockroach alive, hollowing it out bit by bit. The hardened Attenborough veteran might guffaw at this: larvae devouring their living hosts has become a staple of nature documentaries, but that is only the start of it…

How about fungi that slowly take over the host’s body, splitting apart muscle and nerve tissue as they go? The fungus Ophiocordyceps made headlines some time ago when pictures of dead ants with giant fungal stalks growing out of their heads made the rounds on the internet (e.g. in The Atlantic). Some hosts even become so unlucky as to be infected by multiple parasites, each having their own agenda. Others not only kill their host, but then wear their dead bodies as a sort of armour. Still others will change the sex of their host, or sterilize them.

“The hardened Attenborough veteran might guffaw at this: larvae devouring their living hosts has become a staple of nature documentaries”

If the parasite needs to complete its lifecycle in another organism, say a bird, you can count on it changing its host into a suicidal creature that wil make sure to be eaten by that bird. And then there are the parasites that infect colonies of social insects and manipulate not just their host, but other colony members as well, sometimes turning sister against sister in an orgy of bloodshed. There seems to be no end to the cruel and inventive ways in which parasites will exploit and manipulate their hosts. We might not have worms in our eyeballs, fungi growing up our brains, or giant larvae slowly eating our organs to then burst out of our chests. However. As also mentioned by Dunn when shortly discussing Toxoplasma gondii (a parasite of cats), we humans are not exempt (see Never Home Alone: From Microbes to Millipedes, Camel Crickets, and Honeybees, the Natural History of Where We Live).

In the last few chapters, Simon puts forth the claim that the many forms of mind control and neurobiological manipulation by parasites shows that free will is an illusion. Brains are governed by rules that parasites have evolved to ruthlessly exploit. Some readers might disagree, but I think it is a very interesting idea he puts out there.

Although parasite-host manipulation is a serious topic of study in biology (see reference works such as Parasites and the Behavior of Animals or Evolutionary Ecology of Parasites), it is also one of those outlandish topics that lends itself perfectly for popular science books. Simon’s writing is witty:

“Cuvier is most celebrated for breaking it to the world that God really has it out for some critters. The idea of extinction was tough for folks in the 1700s to comprehend, what with the higher power being a supposedly decent guy” (p. 152)

If that kind of irreverence amuses you (and it amuses me), you are guaranteed to have a good laugh reading this book. Plight of the Living Dead is one of those incredibly absorbing books that manages to horrify and entertain in equal measure.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

, ebook or audiobook

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

8 comments