9-minute read

keywords: history of science, paleontology

In modern palaeontology, dinosaurs always hog the limelight. However, as science historian Chris Manias shows in The Age of Mammals, for a long time this was not the case. This scholarly book shows how palaeontology, from its inception in the 1700s until the 1910s, revolved around mammals. In a wide-ranging book that examines historical episodes around the world, Manias convincingly shows that you cannot understand the history of palaeontology without considering mammals.

The Age of Mammals: Nature, Development, & Paleontology in the Long Nineteenth Century, written by Chris Manias, published by the University of Pittsburgh Press in June 2023 (hardback, 473 pages)

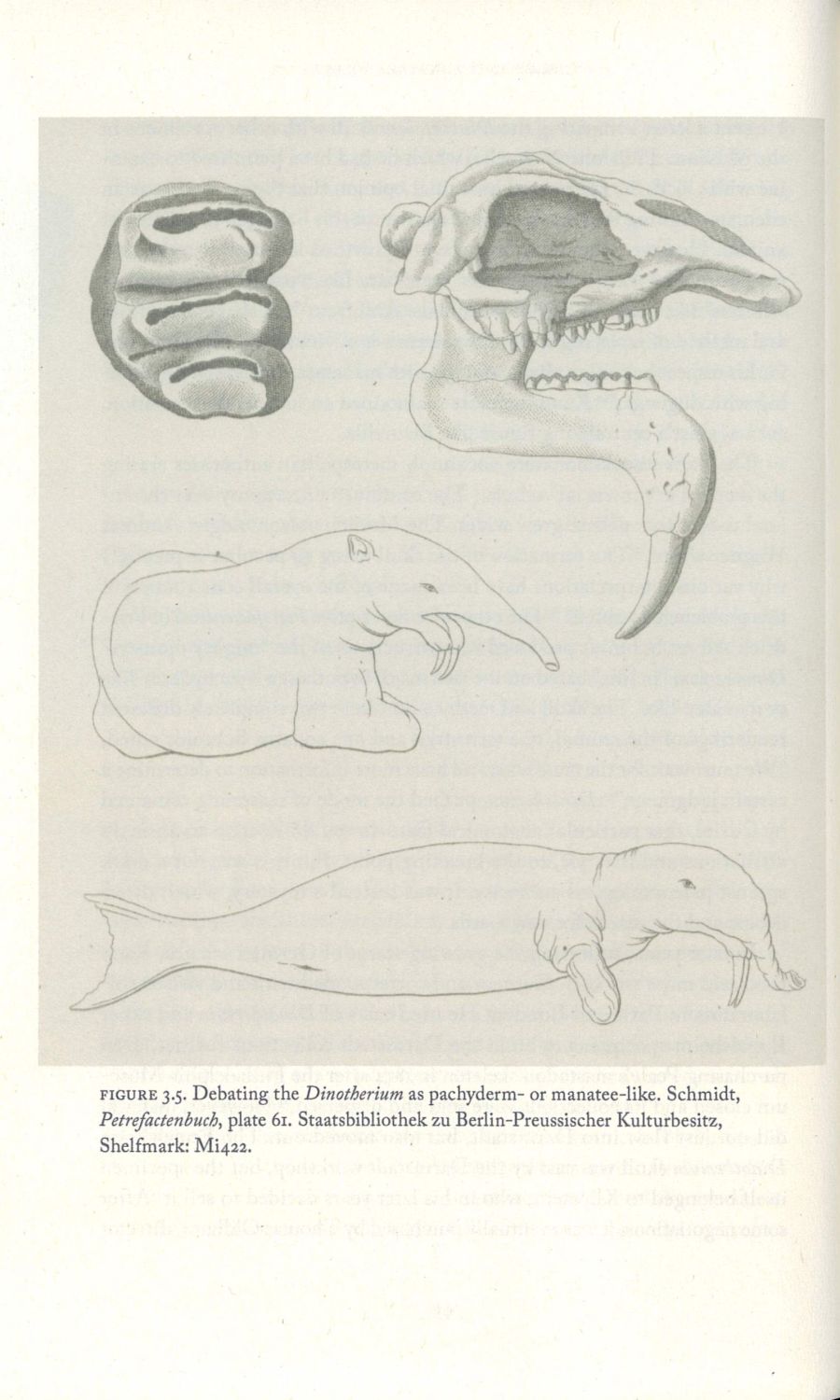

The Age of Mammals is part of the series Intersections: Histories of Environment, Science, and Technology in the Anthropocene and joins the University of Pittsburgh Press’s roster of books on the history of different biological disciplines that they are cranking out this year. Rather than a book about fossil mammals or mammal evolution, this is about the history of palaeontology as a scientific discipline, showing how central the study of fossil mammals has been to its development. One thing to note is that this is not popular science and it took me a few chapters to get into the groove of Manias’s academic writing style. Nothing here is impenetrable, but this is a serious intellectual history. The depth of scholarship is evident from the reference list as Manias has mined the peer-reviewed literature, archives of correspondence, and numerous newspapers and magazines. He has also dug up some remarkable period illustrations and photos that recreate the flavour of this bygone era. In the hope of convincing you why this book is worth your time, I will discuss three major themes that I noticed running through this book.

The most important theme is how fossil mammals were instrumental in revising our understanding of life’s history and evolutionary patterns. We have long clung to the idea of a scala naturae or great chain of being that orders life from lowest to highest. By that logic, mammals were considered superior to all other animals, with humans (of course) placed at the summit. Insights from mammal palaeontology started upending this idea in various ways. Fossil mammals revealed just how diverse life had been, making it increasingly hard to arrange them in any meaningful order. Two notable French scholars who clashed over this were Georges Cuvier, who favoured a non-hierarchical scale, and his less well-remembered former pupil Henri de Blainville, who favoured an explicitly hierarchical scale. Fellow countryman Albert Gaudry, who established a powerful department of palaeontology at the Parisian Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), changed his mind on the scala naturae when he became familiar with South American fossil mammals. Lastly, the discovery of Permian fossils of the mammal ancestor Dicynodon in the South African Karoo region cast doubts on the idea that mammals evolved from reptiles. Maybe that was a too-literal reading of the scala naturae and both groups evolved from amphibians instead? (That already starts sounding more modern, but is still not quite right; Panciroli’s Beasts Before Us and Brusatte’s The Rise and Reign of the Mammals will set you straight on our current understanding of mammal evolution.) It became increasingly clear that “the history of life therefore was not an easy ladder of progress (even if some aspects could be made to fit this narrative)” (p. 207).

The most important theme is how fossil mammals were instrumental in revising our understanding of life’s history and evolutionary patterns. We have long clung to the idea of a scala naturae or great chain of being that orders life from lowest to highest. By that logic, mammals were considered superior to all other animals, with humans (of course) placed at the summit. Insights from mammal palaeontology started upending this idea in various ways. Fossil mammals revealed just how diverse life had been, making it increasingly hard to arrange them in any meaningful order. Two notable French scholars who clashed over this were Georges Cuvier, who favoured a non-hierarchical scale, and his less well-remembered former pupil Henri de Blainville, who favoured an explicitly hierarchical scale. Fellow countryman Albert Gaudry, who established a powerful department of palaeontology at the Parisian Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), changed his mind on the scala naturae when he became familiar with South American fossil mammals. Lastly, the discovery of Permian fossils of the mammal ancestor Dicynodon in the South African Karoo region cast doubts on the idea that mammals evolved from reptiles. Maybe that was a too-literal reading of the scala naturae and both groups evolved from amphibians instead? (That already starts sounding more modern, but is still not quite right; Panciroli’s Beasts Before Us and Brusatte’s The Rise and Reign of the Mammals will set you straight on our current understanding of mammal evolution.) It became increasingly clear that “the history of life therefore was not an easy ladder of progress (even if some aspects could be made to fit this narrative)” (p. 207).

“Fossil mammals revealed just how diverse life had been, making it increasingly hard to arrange them in any meaningful order.”

Closely related to this was the idea that geological history was one of progress and improvement, an idea that has been almost impossible to shake. Though the early age of mammals, the Eocene, was portrayed as a time of harmony, scholarly opinion was also that it had to end. “The history of the mammals, like biblical narratives and human history, could not be locked in early abundance” (p. 181). However, the discovery of Pleistocene ice ages upset the notion of a steady story of progress. Though no plausible mechanism was yet known, the discovery of fossil mammals such as mammoths left no doubt that there had been an ice age, though scholars argued whether there had been one or many. “Linear and cyclical visions of development jostled and persisted” (p. 188). And then there were the poster children of linear evolution, such as elephants and most famously horses. The images that show small horses in a neat linear fashion progressively evolving into larger horses with longer legs and higher-crowned teeth are iconic. The actual story is more complicated and already in 1907 James W. Gidley and Henry Fairfield Osborn of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) wrote a taxonomic revision that concluded as much. Most groups in this sequence had become specialized and left no descendants, showing instead that “evolution had a disjunctive rather than a continuous pattern” (p. 261), though these insights did not necessarily filter through to museum displays.

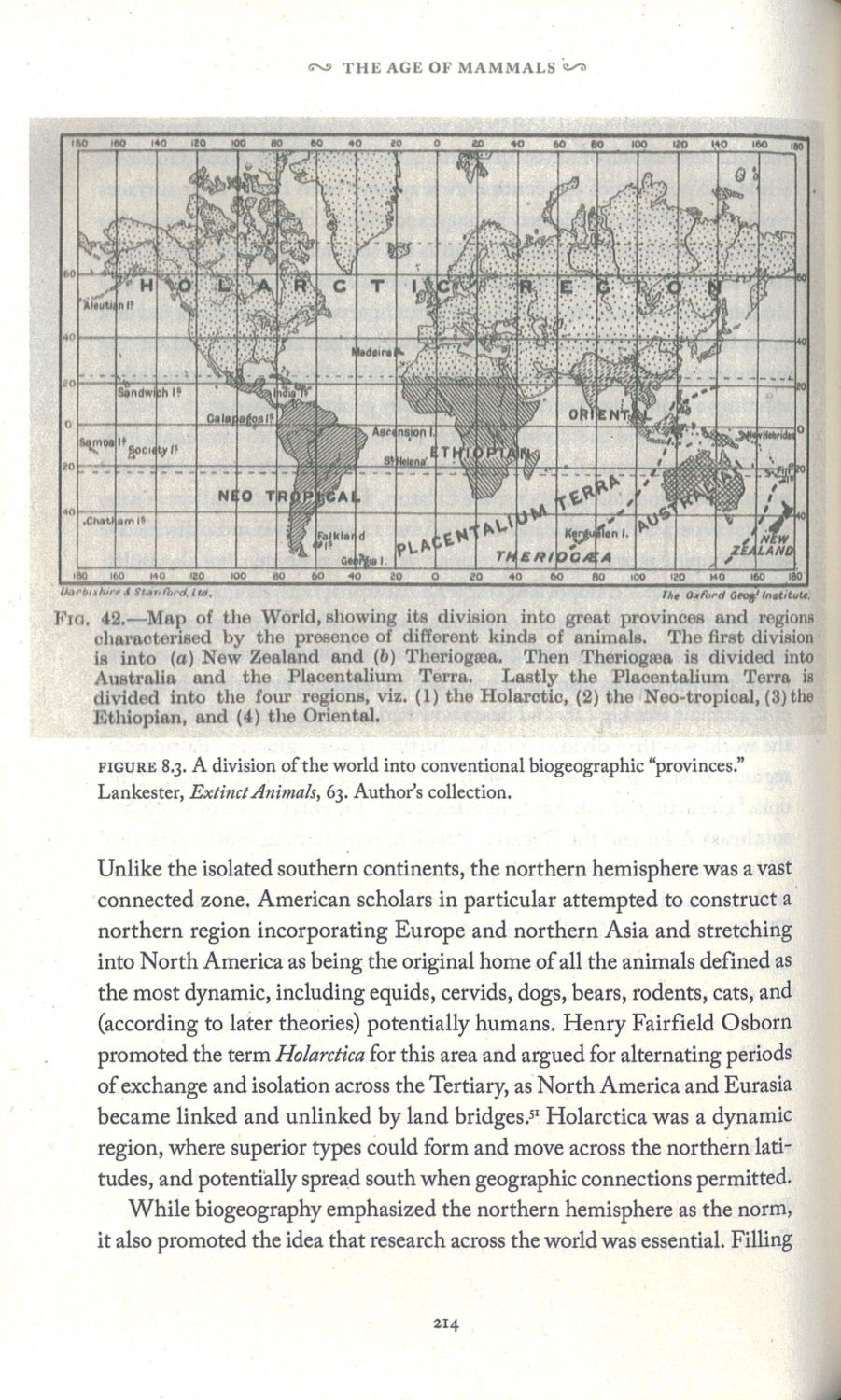

Two further ideas in biology influenced by fossil mammals were extinction and biogeography. It was by studying fossil elephant remains that Cuvier conceived of the idea of extinction. The later realisation that so many large mammals had gone extinct in the Pleistocene raised questions about the role of humans. Were we the baddies, or did it involve many factors, with humans “not the root cause, but the final executioner of the great beasts” (p. 367)? That debate rumbles on even today.  Meanwhile, the distribution of fossil mammals was used to divide the world into six biogeographic zones. Manias flags up a nice bit of subversion here: the realisation that the elephant, that most noble animal, had evolved in Africa suddenly made that continent appear less backward. “Biogeography could be an imperial science, but in doing so could also center modern colonized regions” (p. 333).

Meanwhile, the distribution of fossil mammals was used to divide the world into six biogeographic zones. Manias flags up a nice bit of subversion here: the realisation that the elephant, that most noble animal, had evolved in Africa suddenly made that continent appear less backward. “Biogeography could be an imperial science, but in doing so could also center modern colonized regions” (p. 333).

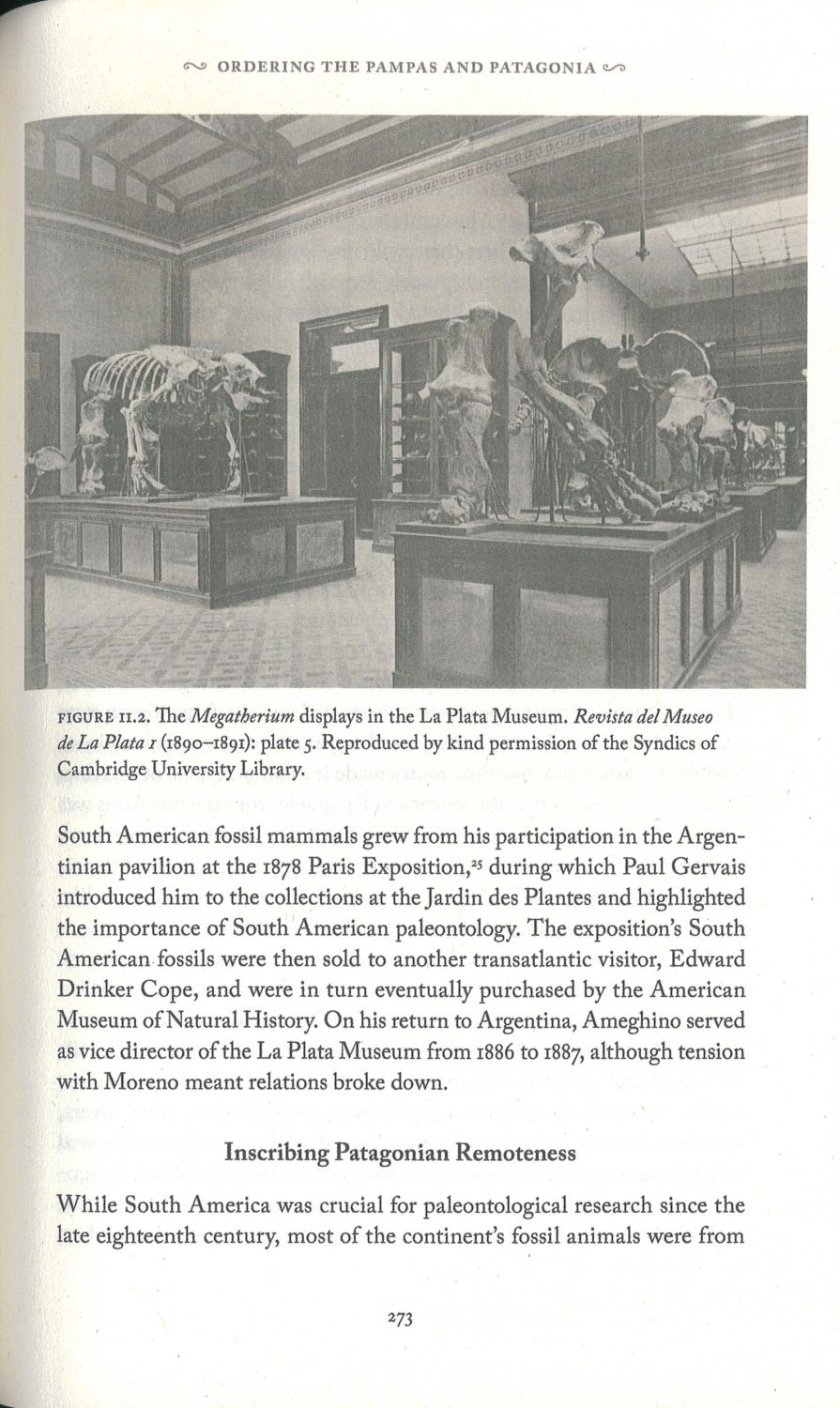

The second major theme of The Age of Mammals is a healthy dose of museology. Manias describes the history of major institutes such as the MNHN, AMNH, and the British Museum (Natural History) (BMNH), the precursor of today’s Natural History Museum, London, all of whom relied on fossil mammal exhibits for some of their fame. He delves into the new museum movement of the 19th century for which the AMNH was a poster child. These large, professionally organized and bureaucratic museums, sponsored by the state and philanthropists, contrasted with the lurid penny museums and travelling exhibits, aiming instead to educate and elevate their public. A well-stocked palaeontological display containing a “canon of fossil mammals” (p. 225) such as mammoths, sabre-toothed tigers, giant deer, and the ground sloth Megatherium, became mandatory. But these museums were not the only game in town. University-based institutions could hold their own by offering educational opportunities, a notable example being how the University of Munich became an international centre of palaeontology under the leadership of Karl Alfred von Zittel. Outside of Europe and North America, some countries successfully drew on their unique fossil mammal fauna. Francisco Moreno and the Ameghino brothers competed with each other to put Argentina and especially Patagonia on the map. But even in the Western United States, small museums set themselves apart not by showcasing the whole history of life, but by building collections of local fossils, such as those from the famous Rancho La Brea tar pits near Los Angeles.

“Manias is finely attuned to all the cultural and historical baggage […] and the amount of ideological assumptions foisted on both animals and humans that he unearths is staggering.”

The third major theme is that Manias is finely attuned to all the cultural and historical baggage. Palaeontology virtually always followed in the wake of colonial expansion, piggybacking on economic activities such as mining, road building, urban construction, or agriculture. It inspired and was inspired by economic and political narratives of improvement, e.g. the idea that under enlightened colonial rule, certain areas could again be made as fruitful as fossil mammals suggested they had once been. Key scholars had horrible views by today’s standards: Edward Drinker Cope was a racist while Osborn supported eugenics. The input of women was marginalized and only a few succeeded in building a professional career, such as Dorothea Bate who held a salaried position at the BMNH in the 1890s. Indigenous knowledge was instrumentalized—basically appropriated to see what it could do for us—with e.g. Aboriginal stories reinterpreted as racial memories of contact with now-extinct mammals. And the contribution of local people and fieldworkers was often belittled or completely erased. However, some clever rereading of history shows they were not always without agency or power. An 1880 report of a fossil collecting trip by the Essex Field Club speaks in patronizing terms of locals showing up to offer fossils for sale. What this instead shows, Manias argues, is that they knew how to recognize, extract, and preserve fossils. Similarly, scholars were utterly dependent on locals for excavations, logistics, and supplies, and the frequent whining of white men about the natives (e.g. during fossil collecting expeditions in Fayum, Egypt) revealed that locals held trump cards and played them. Manias leaves no opportunity unused to highlight all of the above disturbing history, and the amount of ideological assumptions foisted on both animals and humans that he unearths is staggering. In my opinion, he is neither judgemental nor moralizing, instead striking the right tone by putting people and events in context.

they were not always without agency or power. An 1880 report of a fossil collecting trip by the Essex Field Club speaks in patronizing terms of locals showing up to offer fossils for sale. What this instead shows, Manias argues, is that they knew how to recognize, extract, and preserve fossils. Similarly, scholars were utterly dependent on locals for excavations, logistics, and supplies, and the frequent whining of white men about the natives (e.g. during fossil collecting expeditions in Fayum, Egypt) revealed that locals held trump cards and played them. Manias leaves no opportunity unused to highlight all of the above disturbing history, and the amount of ideological assumptions foisted on both animals and humans that he unearths is staggering. In my opinion, he is neither judgemental nor moralizing, instead striking the right tone by putting people and events in context.

The Age of Mammals is a comprehensive and revelatory history that is full of fascinating stories from around the world. It is also an incredibly welcome addition to the literature. Panciroli and Brusatte touched on some of this history in their books, but most books on the history of palaeontology, such as The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush, or the previously reviewed American Dinosaur Abroad (also from Pittsburgh) and Assembling the Dinosaur all focus on a certain group of extinct reptiles. Thus, I warmly recommend this to readers interested in the history of palaeontology and, more generally, science history and museology.

If want to hear some more, Manias was recently interviewed on the Fossils & Fiction podcast.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

One comment